Mildly interesting

-

"Three minutes from the moon, alarms screamed through the cabin—but one woman's code, written with less memory than a text message, made the split-second decision that saved them."

July 20, 1969. 240,000 miles from Earth.

Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin are descending toward the lunar surface in the Eagle lander. Millions watch on television. The entire world holds its breath.

Then, alarms start screaming.

1201. 1202. EXECUTIVE OVERFLOW.

The computer is dying. Overloaded. Failing at the worst possible moment.

Mission Control goes silent. Should they abort? Decades of work, billions of dollars, humanity's greatest dream—all threatened by a computer error three minutes from touchdown.

But the landing continues.

Because 240,000 miles away, back on Earth, a 33-year-old woman had already solved this problem.

Her name was Margaret Hamilton, and she had spent years writing the code that would either save these astronauts or doom them.

In 1969, Margaret Hamilton was doing something almost nobody understood: writing software that would navigate humans to another world.

She was the Director of the Software Engineering Division at MIT's Instrumentation Laboratory, leading the team responsible for the Apollo Guidance Computer—the onboard brain that would control a spacecraft traveling farther from home than any human had ever ventured.

The Apollo computer had 72 kilobytes of memory.

Let that sink in. A single photo on your phone today uses more memory than the entire computer system that landed humans on the moon. They were programming a machine less powerful than a modern calculator to perform one of the most complex tasks in human history.

And they were doing it with primitive tools—feeding punch cards into room-sized computers, one line of code at a time. No error messages that made sense. No "undo" button. No Google to search for answers.

Every single line had to be perfect.

Because out there, 240,000 miles from Earth, there was no tech support. No software update. No second chance.

If her code failed, three astronauts would die in the vacuum of space, and humanity's greatest dream would become its most public tragedy.

Hamilton understood something most engineers at NASA didn't grasp yet: software wasn't just a tool—it was the foundation everything else depended on.

While some colleagues dismissed programming as clerical work, something secondary to the "real" engineering of rockets and spacecraft, Hamilton insisted software deserved the same rigor, testing, and respect as any other discipline.

She demanded resilience. Error detection. Recovery systems that could handle the unexpected.

Some thought she was overthinking it. Overcomplicating things.

Margaret Hamilton knew better.

She built into her code something revolutionary: the ability to prioritize. To make decisions. To adapt when everything went wrong.

She programmed the computer to think: If I'm overwhelmed, what's essential for survival? What can wait? What must continue no matter what?

It seemed like paranoia.

Until July 20, 1969, when it became prophecy.

As Armstrong and Aldrin descended toward the Sea of Tranquility, the Eagle's rendezvous radar—which should have been turned off—was feeding unnecessary data into the computer. The system was being asked to do too much at once.

1201. Executive overflow.

The alarm meant: I'm drowning. I can't process everything. I might crash.

At Mission Control, controllers frantically checked their screens. The flight director demanded answers: Go or no-go?

Jack Garman, a 24-year-old guidance officer, remembered something from months of training. These alarms meant the computer was shedding non-essential tasks to focus on what mattered.

Hamilton's code was doing exactly what she'd designed it to do.

"We're go on that alarm," Garman said.

The landing continued.

The alarms kept blaring—1202, 1201, 1202—but Armstrong kept descending. The computer kept calculating. Hamilton's software kept prioritizing, adapting, surviving.

At 4:17 PM Eastern Time, Armstrong's voice crackled across 240,000 miles of space:

"The Eagle has landed."

Humanity had touched another world.

And it happened because one woman had anticipated the crisis, engineered resilience into every line of code, and refused to accept "good enough" when three lives hung in the balance.

The famous photograph captured it all: Margaret Hamilton standing next to a stack of printed code—her Apollo program—stacked taller than she was.

That tower of paper represented something invisible but essential. The hidden architecture that made the impossible possible.

After Apollo 11, the astronauts became legends. The rocket engineers got recognition. But the woman whose code guided them to the moon and back?

She was a footnote. Overlooked. Underestimated.

For 47 years.

In 2016, President Barack Obama finally awarded Margaret Hamilton the Presidential Medal of Freedom—the nation's highest civilian honor—acknowledging her contribution to one of humanity's greatest achievements.

But her legacy was already written in every line of code we depend on today.

Hamilton didn't just write software—she defined what software engineering could be. She proved it wasn't clerical work but a rigorous discipline requiring precision, creativity, and foresight. She coined the very term "software engineering" to give her field the respect it deserved.

Every app on your phone, every computer running hospitals and airplanes and power grids, every system that keeps modern civilization functioning—they all rest on the foundation Margaret Hamilton built.

She was 33 years old, working in a field that barely existed, solving problems no one had ever faced, with technology that seems laughable by today's standards.

And she did it so brilliantly that when alarms screamed and computers overloaded and everything seemed to be failing, her code made the split-second decisions that saved three lives and fulfilled humanity's greatest dream.

Margaret Hamilton didn't go to the moon.

But without her, no one would have.

And the next time you write a line of code, debug a program, or trust your life to software flying you across the country, remember:

Every system that thinks, adapts, and survives when things go wrong owes a debt to a woman who refused to let three astronauts die because of an oversight.

She taught computers to make the impossible possible.

One line of code at a time. -

"Three minutes from the moon, alarms screamed through the cabin—but one woman's code, written with less memory than a text message, made the split-second decision that saved them."

July 20, 1969. 240,000 miles from Earth.

Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin are descending toward the lunar surface in the Eagle lander. Millions watch on television. The entire world holds its breath.

Then, alarms start screaming.

1201. 1202. EXECUTIVE OVERFLOW.

The computer is dying. Overloaded. Failing at the worst possible moment.

Mission Control goes silent. Should they abort? Decades of work, billions of dollars, humanity's greatest dream—all threatened by a computer error three minutes from touchdown.

But the landing continues.

Because 240,000 miles away, back on Earth, a 33-year-old woman had already solved this problem.

Her name was Margaret Hamilton, and she had spent years writing the code that would either save these astronauts or doom them.

In 1969, Margaret Hamilton was doing something almost nobody understood: writing software that would navigate humans to another world.

She was the Director of the Software Engineering Division at MIT's Instrumentation Laboratory, leading the team responsible for the Apollo Guidance Computer—the onboard brain that would control a spacecraft traveling farther from home than any human had ever ventured.

The Apollo computer had 72 kilobytes of memory.

Let that sink in. A single photo on your phone today uses more memory than the entire computer system that landed humans on the moon. They were programming a machine less powerful than a modern calculator to perform one of the most complex tasks in human history.

And they were doing it with primitive tools—feeding punch cards into room-sized computers, one line of code at a time. No error messages that made sense. No "undo" button. No Google to search for answers.

Every single line had to be perfect.

Because out there, 240,000 miles from Earth, there was no tech support. No software update. No second chance.

If her code failed, three astronauts would die in the vacuum of space, and humanity's greatest dream would become its most public tragedy.

Hamilton understood something most engineers at NASA didn't grasp yet: software wasn't just a tool—it was the foundation everything else depended on.

While some colleagues dismissed programming as clerical work, something secondary to the "real" engineering of rockets and spacecraft, Hamilton insisted software deserved the same rigor, testing, and respect as any other discipline.

She demanded resilience. Error detection. Recovery systems that could handle the unexpected.

Some thought she was overthinking it. Overcomplicating things.

Margaret Hamilton knew better.

She built into her code something revolutionary: the ability to prioritize. To make decisions. To adapt when everything went wrong.

She programmed the computer to think: If I'm overwhelmed, what's essential for survival? What can wait? What must continue no matter what?

It seemed like paranoia.

Until July 20, 1969, when it became prophecy.

As Armstrong and Aldrin descended toward the Sea of Tranquility, the Eagle's rendezvous radar—which should have been turned off—was feeding unnecessary data into the computer. The system was being asked to do too much at once.

1201. Executive overflow.

The alarm meant: I'm drowning. I can't process everything. I might crash.

At Mission Control, controllers frantically checked their screens. The flight director demanded answers: Go or no-go?

Jack Garman, a 24-year-old guidance officer, remembered something from months of training. These alarms meant the computer was shedding non-essential tasks to focus on what mattered.

Hamilton's code was doing exactly what she'd designed it to do.

"We're go on that alarm," Garman said.

The landing continued.

The alarms kept blaring—1202, 1201, 1202—but Armstrong kept descending. The computer kept calculating. Hamilton's software kept prioritizing, adapting, surviving.

At 4:17 PM Eastern Time, Armstrong's voice crackled across 240,000 miles of space:

"The Eagle has landed."

Humanity had touched another world.

And it happened because one woman had anticipated the crisis, engineered resilience into every line of code, and refused to accept "good enough" when three lives hung in the balance.

The famous photograph captured it all: Margaret Hamilton standing next to a stack of printed code—her Apollo program—stacked taller than she was.

That tower of paper represented something invisible but essential. The hidden architecture that made the impossible possible.

After Apollo 11, the astronauts became legends. The rocket engineers got recognition. But the woman whose code guided them to the moon and back?

She was a footnote. Overlooked. Underestimated.

For 47 years.

In 2016, President Barack Obama finally awarded Margaret Hamilton the Presidential Medal of Freedom—the nation's highest civilian honor—acknowledging her contribution to one of humanity's greatest achievements.

But her legacy was already written in every line of code we depend on today.

Hamilton didn't just write software—she defined what software engineering could be. She proved it wasn't clerical work but a rigorous discipline requiring precision, creativity, and foresight. She coined the very term "software engineering" to give her field the respect it deserved.

Every app on your phone, every computer running hospitals and airplanes and power grids, every system that keeps modern civilization functioning—they all rest on the foundation Margaret Hamilton built.

She was 33 years old, working in a field that barely existed, solving problems no one had ever faced, with technology that seems laughable by today's standards.

And she did it so brilliantly that when alarms screamed and computers overloaded and everything seemed to be failing, her code made the split-second decisions that saved three lives and fulfilled humanity's greatest dream.

Margaret Hamilton didn't go to the moon.

But without her, no one would have.

And the next time you write a line of code, debug a program, or trust your life to software flying you across the country, remember:

Every system that thinks, adapts, and survives when things go wrong owes a debt to a woman who refused to let three astronauts die because of an oversight.

She taught computers to make the impossible possible.

One line of code at a time.@Mik said in Mildly interesting:

While some colleagues dismissed programming as clerical work, something secondary to the "real" engineering of rockets and spacecraft, Hamilton insisted software deserved the same rigor, testing, and respect as any other discipline.

Ironically if that hadn’t been the perception in the 50s and 60s there wouldn’t have been all these female coders at NASA at this time.

-

Was she the inspiration for the Linux logo?

-

@jon-nyc said in Mildly interesting:

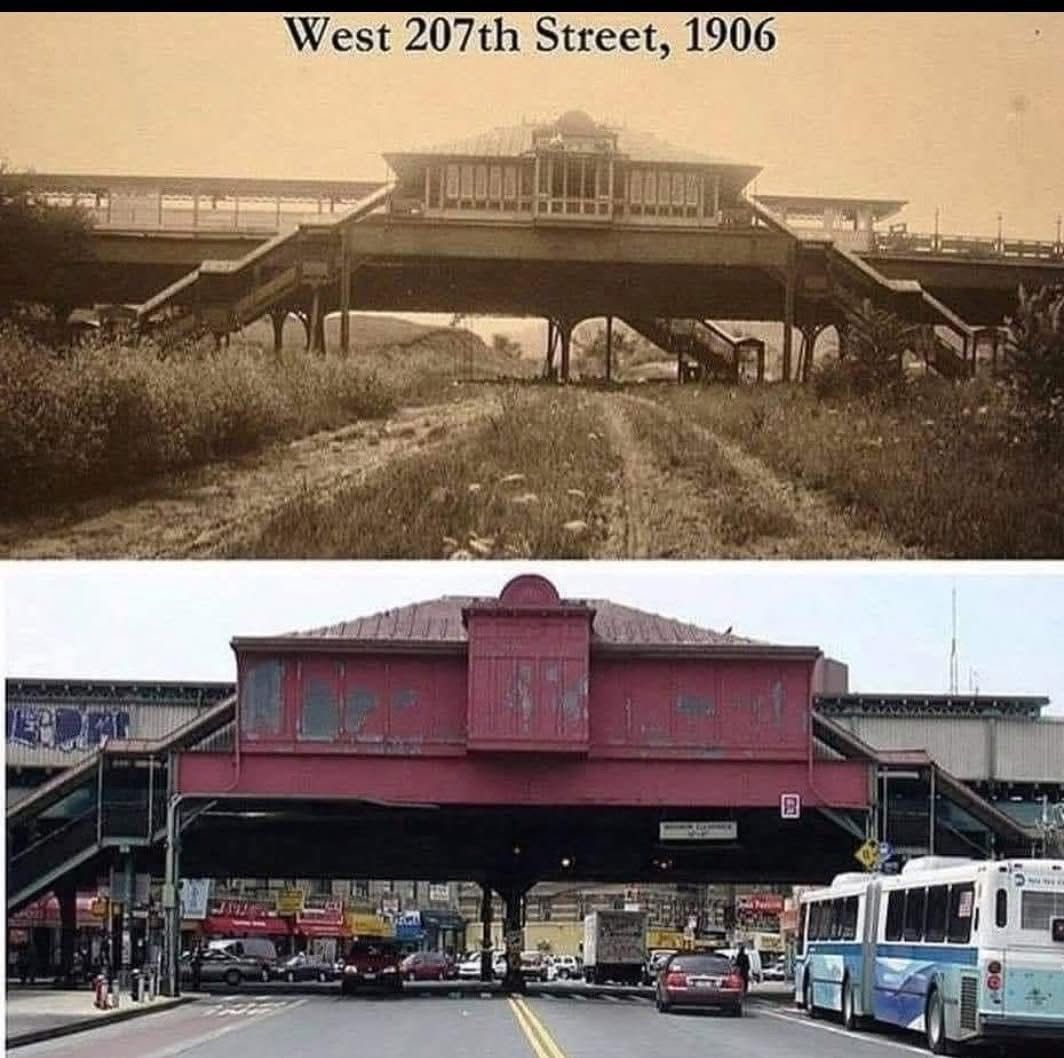

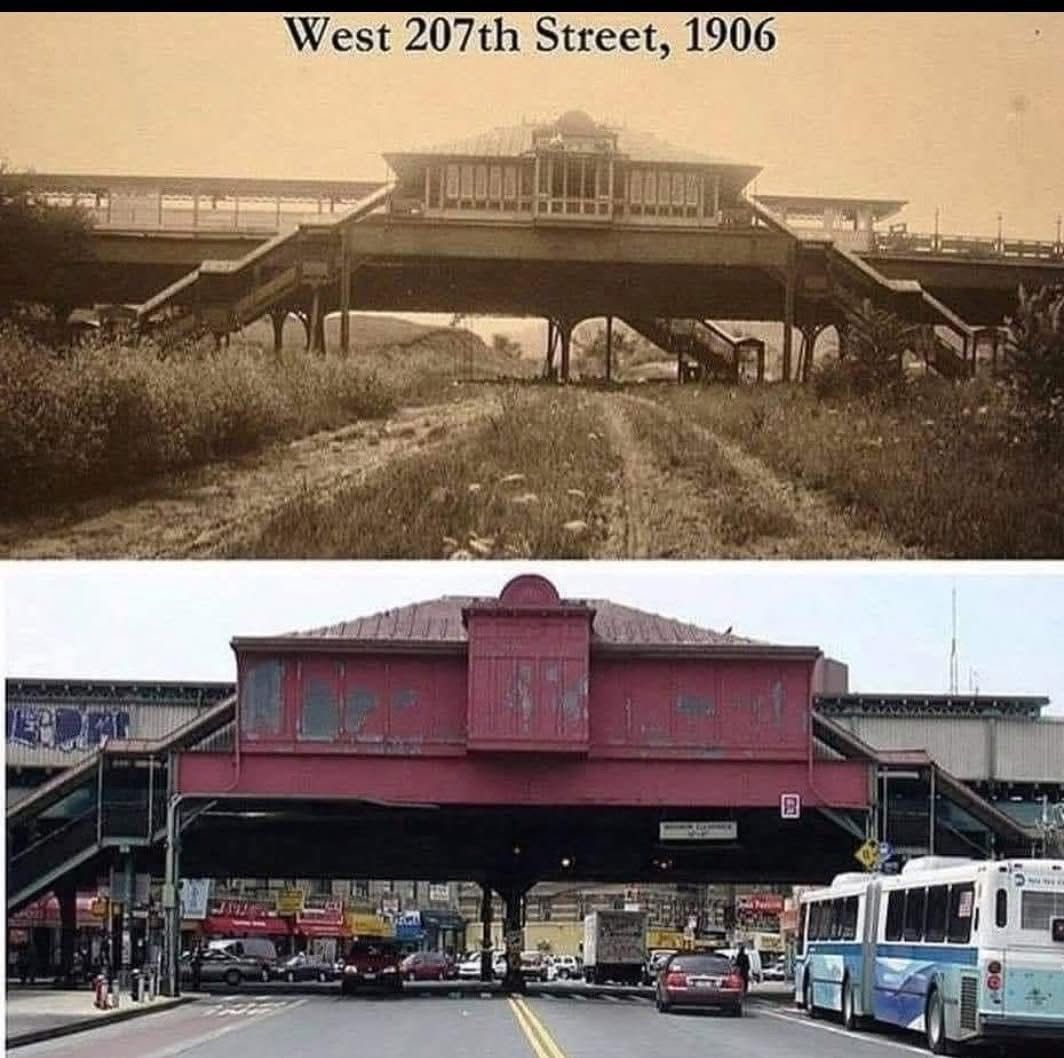

207th and Broadway in Manhattan.

That's pretty much the reverse of all the pictures I see on Facebook for my hometown, which has rather gone downhill of late.

-

@jon-nyc said in Mildly interesting:

207th and Broadway in Manhattan.

That's pretty much the reverse of all the pictures I see on Facebook for my hometown, which has rather gone downhill of late.

@Doctor-Phibes said in Mildly interesting:

That's pretty much the reverse of all the pictures I see on Facebook for my hometown, which has rather gone downhill of late.

Your moving in and the decline - hope you pointed out that correlation does not equate to causation.

-

Im just wrapping my head around the idea that parts of broadway were unpaved when my grandfather arrived.