Trumpenomics

-

When Bezos allegedly bent the knee to Trump before the election, he was clear that he wanted WaPo editorials to support free markets. Being anti-tariff is on-brand, and principled, and should probably earn him some credit from those who think he was just supplicating before Trump.

-

-

@jon-nyc said in Trumpenomics:

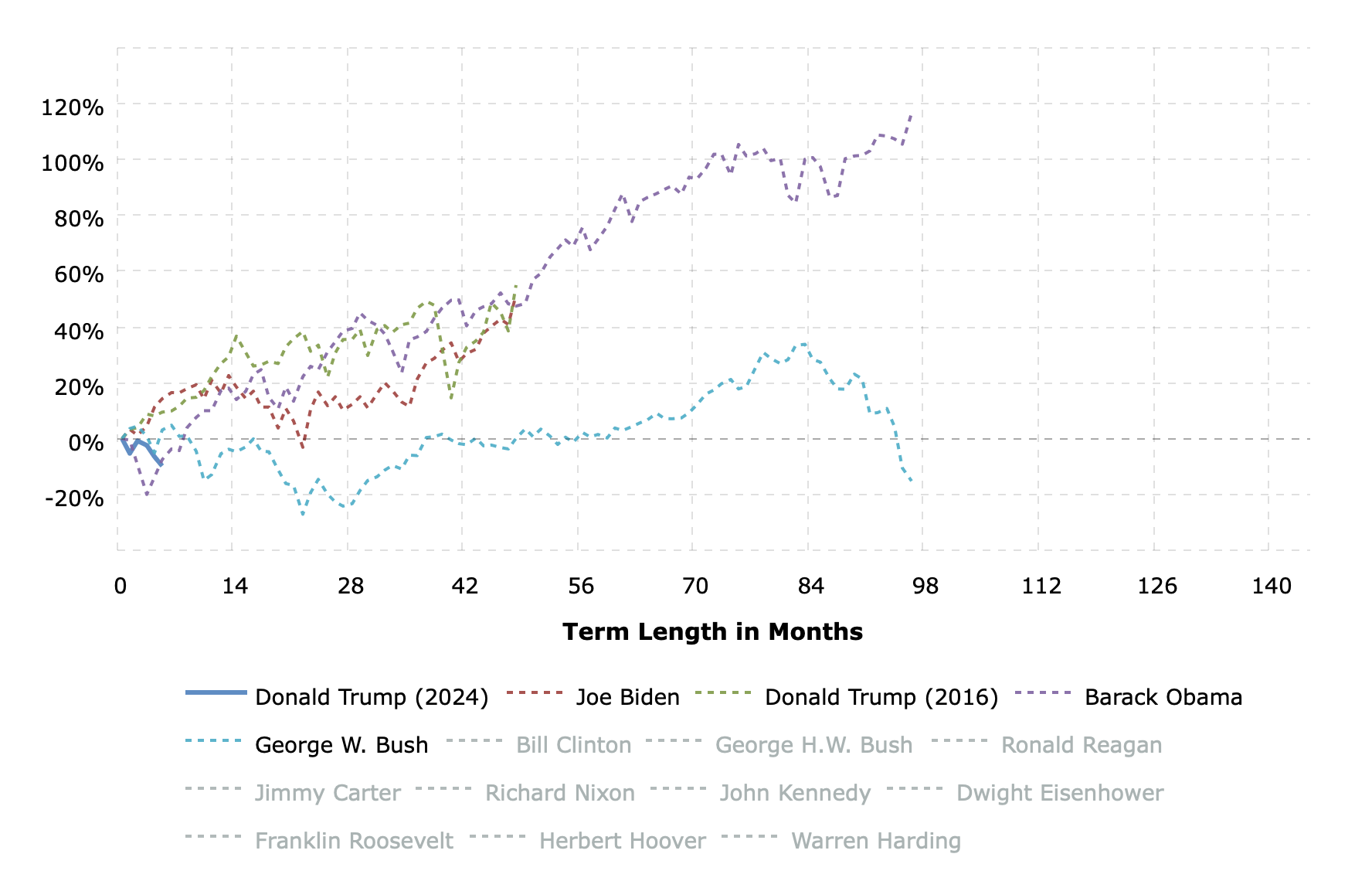

The S&P500 experienced its biggest first 100 day loss for a President since 1973, per WSJ

Here is the Dow Jones showing returns since Election Day. To be fair to President Trump, he is about the same as President Obama at this point, but I am not sure the trend of President Trump will match the trend of President Obama.

-

I'm kind of hoping they start using the word 'resignation' soon, but it doesn't seem very likely based on his transcendental performance.

-

@Horace said in Trumpenomics:

@Mik said in Trumpenomics:

@Horace said in Trumpenomics:

@Axtremus said in Trumpenomics:

#3 can happen after the Democrats win big in the mid-term.

Two years of this madness will be enough time for the Dems to gain credit for saving the economy, if they end the tariffs. If they do it now, with some GOP help, Trump takes only a small hit, and he'll be able to retail the idea that the tariffs would have worked if they'd been given a chance.

As Matt Yglesias opens today's email with:

Well, “Liberation Day” has arrived and it sucks, but Trump’s taste for terrible trade policy may be American democracy’s best hope, so I have mixed feelings about the whole thing.

I assume these sorts of mixed feelings are shared by lots of Democrats, and so I'm a little surprised they would try to end the tariffs right now. But once the legislation is on the floor, which I hope happens as soon as possible, I guess they'll have to vote to end them, or take responsibility for them.

And nowhere does Mr. Yglesias state what he would suggest doing about the problems Trump is trying, however well or badly, to address. he just snipes from the gallery. Pundits gotta pundit.

It's not hard to meaningfully criticize, when doing nothing would have been much better than doing something. Your premise that Trump is addressing a problem, is flawed. Trade imbalances are not a problem. People in poorer countries doing America's dirty work making cheap products and selling them to us, is not a problem.

That's not the problem he's trying to fix. It's manufacturing capability as national security. All this rise of the middle class and good jobs is smoke. We need more steel and aluminum made here, alongside chips, etc.

I'm not crazy about his methods, but then we had a pretty good idea it would be crudely done. Finesse is not his middle name. He may end up being viewed as a very good or very bad president, but no one will be neutral.

@Mik said in Trumpenomics:

We need more steel and aluminum made here, alongside chips, etc.https://fortune.com/article/tariffs-high-prices-aluminum-economy/

Aluminum is not a luxury good. It’s a foundational metal—indispensable to energy transmission, cars, construction, packaging, and even military products. And yet, despite rising demand, U.S. production capacity has all but collapsed.

At the turn of the millennium, the United States was the global leader in aluminum production. Twenty-three smelters operated nationwide. Today, only four remain active—and they are not running at full capacity. The closure of key plants in recent years has hollowed out a once-robust industry.

I work at an organization that researches American industry, and when we examined aluminum supply chains, we found something sobering. A new report from Industrious Labs forecasts that domestic demand for primary aluminum could surge as much as 40% by 2035. That’s a staggering increase for a material so deeply embedded in nearly every aspect of modern life—and we are alarmingly unprepared to meet it.

Currently, 82% of the primary aluminum Americans now consume is imported, making the U.S. the world’s largest net importer of aluminum. Over half comes from Canada, a friendly and reliable partner—for now. But with global markets tightening, anti-American sentiment in Canada rising, and European trade regulations poised to reroute Canadian supply to Europe, the U.S. may soon find itself at the back of the line.

In other words, we are on the cusp of an aluminum crunch.

According to the Industrious Labs report, the U.S. could need up to 6.4 million metric tons of primary aluminum per year by 2035. That’s far beyond what we can produce domestically today. If the U.S. can’t get the aluminum it needs, then the consequences will be stark: Prices for cars, power lines, packaging, and even clean energy infrastructure could rise sharply as manufacturers scramble for limited supply.

-

@Mik said in Trumpenomics:

We need more steel and aluminum made here, alongside chips, etc.https://fortune.com/article/tariffs-high-prices-aluminum-economy/

Aluminum is not a luxury good. It’s a foundational metal—indispensable to energy transmission, cars, construction, packaging, and even military products. And yet, despite rising demand, U.S. production capacity has all but collapsed.

At the turn of the millennium, the United States was the global leader in aluminum production. Twenty-three smelters operated nationwide. Today, only four remain active—and they are not running at full capacity. The closure of key plants in recent years has hollowed out a once-robust industry.

I work at an organization that researches American industry, and when we examined aluminum supply chains, we found something sobering. A new report from Industrious Labs forecasts that domestic demand for primary aluminum could surge as much as 40% by 2035. That’s a staggering increase for a material so deeply embedded in nearly every aspect of modern life—and we are alarmingly unprepared to meet it.

Currently, 82% of the primary aluminum Americans now consume is imported, making the U.S. the world’s largest net importer of aluminum. Over half comes from Canada, a friendly and reliable partner—for now. But with global markets tightening, anti-American sentiment in Canada rising, and European trade regulations poised to reroute Canadian supply to Europe, the U.S. may soon find itself at the back of the line.

In other words, we are on the cusp of an aluminum crunch.

According to the Industrious Labs report, the U.S. could need up to 6.4 million metric tons of primary aluminum per year by 2035. That’s far beyond what we can produce domestically today. If the U.S. can’t get the aluminum it needs, then the consequences will be stark: Prices for cars, power lines, packaging, and even clean energy infrastructure could rise sharply as manufacturers scramble for limited supply.

From article:

Over half comes from Canada, a friendly and reliable partner—for now. But with global markets tightening, anti-American sentiment in Canada rising, and European trade regulations poised to reroute Canadian supply to Europe, the U.S. may soon find itself at the back of the line.

I wonder how that came to be?