Mildly interesting

-

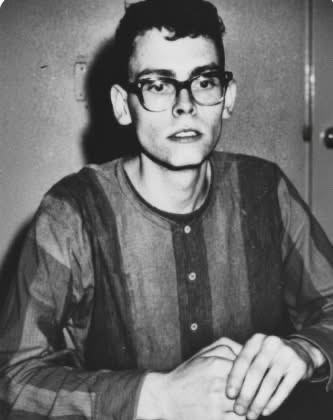

They called him the stupidest prisoner they'd ever seen. He was actually the most dangerous man in the camp.

April 6, 1967. The USS Canberra unleashed its guns during a night bombardment in the Gulf of Tonkin. The blast from the ship's own massive cannons sent 20-year-old Seaman Douglas Hegdahl flying overboard into the dark waters of the South China Sea.

The farm boy from South Dakota swam through the night. Twelve hours. No rescue boat found him. Instead, North Vietnamese fishermen pulled him from the water at dawn and turned him over to military authorities.

Within days, Hegdahl found himself inside Hỏa Lò Prison, the notorious facility American POWs grimly called the Hanoi Hilton. Interrogators immediately began their work, demanding information about ship movements, military operations, classified details.

But Hegdahl had a problem. And then he had an idea.

He was a low-ranking enlisted sailor with no access to secrets. He knew nothing valuable. So he decided to become someone they would never take seriously. He would become invisible by being unforgettable for all the wrong reasons.

He exaggerated his rural accent until it was nearly incomprehensible. He stared blankly when asked questions. He moved slowly, as if struggling to understand basic instructions. When interrogators shoved anti-American propaganda documents in front of him and demanded he sign, Hegdahl shook his head sadly.

"I can't read," he said. "Never learned how."

The guards were stunned. They didn't believe him at first. So they tried to teach him, convinced that proving his literacy would break his resistance. Day after day, they attempted to drill letters and words into his head.

Hegdahl sat through every lesson looking confused and overwhelmed. He couldn't seem to remember the letter "A" from one day to the next. His tutors grew increasingly frustrated. After weeks of failure, they gave up entirely.

They nicknamed him "The Incredibly Stupid One."

And then they made their fatal mistake.

Believing he was a harmless simpleton incapable of understanding anything, the guards gave him unprecedented freedom. They assigned him to sweep courtyards and common areas—privileges no other American prisoner possessed. While hardened officers remained locked in cells, enduring torture and isolation, this "stupid" farm boy wandered the compound with a broom.

He wasn't sweeping. He was gathering intelligence.

He sabotaged five North Vietnamese military trucks by pouring dirt into their gas tanks when guards weren't looking. He observed guard patterns, security weaknesses, and prison layouts. Most importantly, he became something extraordinary: a human database.

Fellow prisoner Joe Crecca taught him a mnemonic technique. Set information to music, Crecca explained, and the mind never forgets. Hegdahl chose the simplest tune he knew: "Old MacDonald Had a Farm."

Every single day while pushing his broom across prison courtyards, Hegdahl sang silently in his head. Each verse contained the name, rank, capture date, and personal details of another American POW. Captain Smith... E-I-E-I-O... Lieutenant Johnson... E-I-E-I-O.

Two hundred fifty-six men. He memorized them all.

In August 1969, the North Vietnamese decided to release three American prisoners as a propaganda gesture meant to show "humanitarian treatment." They deliberately chose men they believed would be useless to US intelligence operations.

They chose Hegdahl because they were certain he was too stupid to tell anyone anything meaningful.

Hegdahl didn't want to go. The POWs had an unbreakable code: nobody goes home until everyone goes home. But Lieutenant Commander Dick Stratton, the senior ranking prisoner, gave him a direct order.

"You are the memory," Stratton told him. "You have to get the names out."

When Hegdahl stepped off the plane onto American soil, he didn't just speak. He sang.

He recited the names, ranks, and details of 256 American servicemen who the US government had listed as missing or presumed dead. Families who had spent years without information suddenly had confirmation their loved ones were alive. Military intelligence gained crucial data about who was imprisoned and where.

But Hegdahl wasn't finished.

He traveled to the Paris Peace Talks where American and North Vietnamese negotiators were attempting to end the war. He confronted the North Vietnamese delegation directly, providing detailed testimony about torture methods, prison conditions, and violations of the Geneva Conventions. His testimony was credible, specific, and impossible to dismiss.

The "stupid" prisoner nobody had paid attention to became the witness who exposed their lies to the world.

Douglas Hegdahl returned to the United States Navy as an instructor in the Navy's SERE program (Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape). He taught generations of service members the most important lesson his story offered:

The most dangerous person in the room isn't always the strongest or the loudest or the most obviously threatening.

Sometimes it's the one everyone underestimates.

The one nobody sees coming. -

@mik. Two very cool stories

-

Tomatoes, along with potatoes, corn, and peppers, are all native to the Americas, so they didn’t exist in Europe before 1492.

The Romans were eating things like olives, lentils, cabbage, and a surprising amount of fish sauce called garum, but no pizza toppings or spaghetti sauce as we know them.

Tomato sauce as we know it in Italy didn’t appear until the early 18th century. Even though tomatoes arrived in southern Europe after Columbus brought them from the Americas in the 16th century, they were initially grown mostly as ornamental plants because some Europeans thought they were poisonous.

It wasn’t until the 1600s and 1700s that people in Naples and other parts of southern Italy began experimenting with cooking tomatoes. By around the 1730s, recipes for a simple tomato-based sauce started appearing in Neapolitan cookbooks, usually combined with olive oil, garlic, and herbs. This eventually evolved into the classic Italian tomato sauces we associate with pasta today.

-

60 is the new 47. Look how rickles and carson looked at 47. Like 60 year olds today. I wonder why things have changed so much.

Link to video -

60 is the new 47. Look how rickles and carson looked at 47. Like 60 year olds today. I wonder why things have changed so much.

Link to video@Horace said in Mildly interesting:

I wonder why things have changed so much.

Tobacco and alcohol probably didn't help much.