Mildly interesting

-

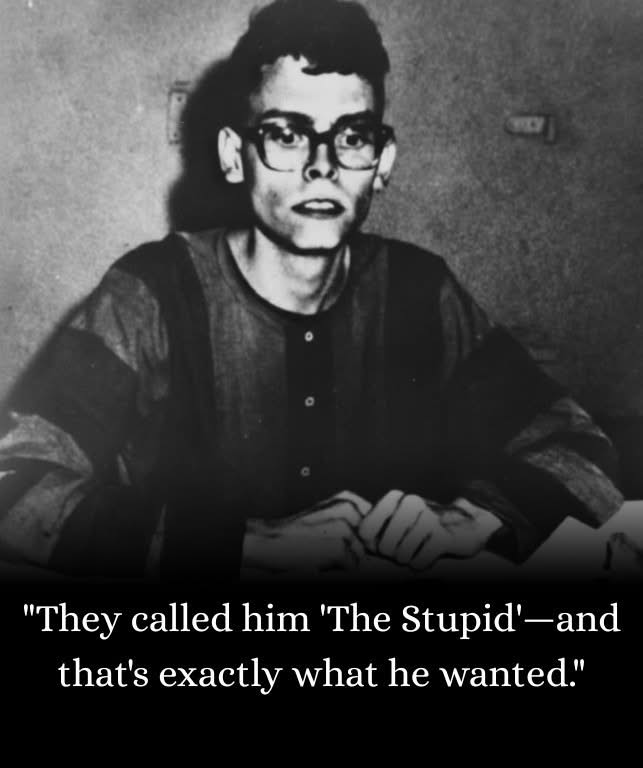

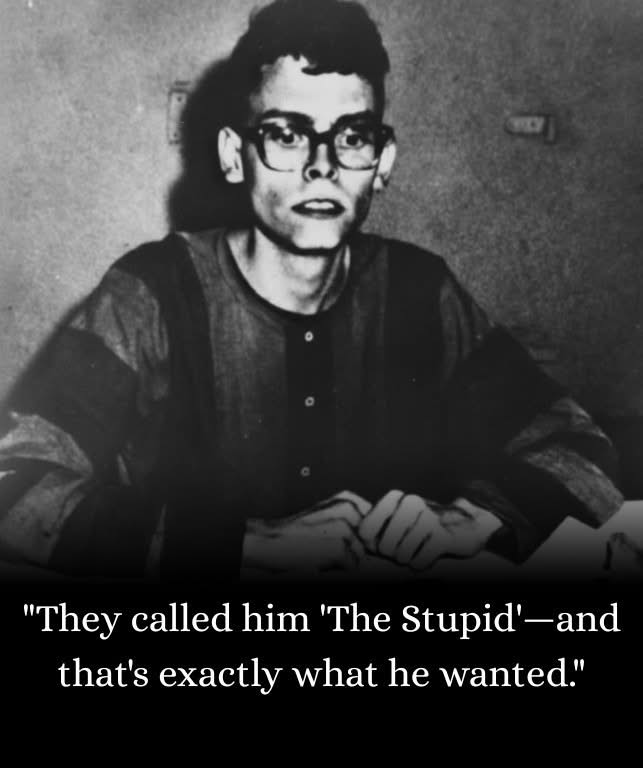

They called him "The Stupid"—and that's exactly what he wanted.

When Navy sailor Douglas Hegdahl was captured during the Vietnam War and thrown into the infamous Hanoi Hilton prison camp, he made a decision that would save hundreds of lives. He would play dumb.

Hegdahl acted confused, clumsy, harmless. His captors laughed at him. They gave him freedom to wander because they thought he was too simple to be a threat.

They were catastrophically wrong.

While pretending to stumble around, Hegdahl was secretly pouring dirt into enemy truck fuel tanks, quietly sabotaging their operations. But his greatest act of defiance was invisible: he began memorizing every detail about his fellow prisoners—names, capture dates, conditions—information the enemy deliberately kept hidden from the world.

256 names. 256 faces. 256 families who deserved to know their loved ones were alive.

How did he remember them all? He set the information to the tune of "Old MacDonald Had a Farm," singing it silently in his head, day after day.

In 1969, Hegdahl was released as part of a propaganda stunt. The North Vietnamese thought they were freeing a harmless fool.

Instead, they released one of the war's most valuable intelligence assets. The moment he reached American soil, Hegdahl delivered every name, every detail, ensuring that 256 prisoners would not be forgotten.

Sometimes the most powerful weapon isn't strength—it's the courage to let others underestimate you.

@Mik said in Mildly interesting:

They called him "The Stupid"—and that's exactly what he wanted...

Actually, during the Vietnam War there was a program to enlist low IQ people and send them into combat.

[McNamara's Morons](https://en.wikipedia.org › wiki › Project_100,000)

-

@jon-nyc said in Mildly interesting:

Among the statistical correlations with this are amusing oddities such as the phenotypes of the antifa sorts harassing ICE officers, and the phenotypes of the ICE officers. It's wealthier white kids harassing working class minorities.

Another amusing correlation that made its way around conservative media was the makeup of the No Kings protests. Lots of elderly white people.

-

Thankfully, the President is emptying the prisons of white collar criminals - making more room for true felons such as this woman who purchased baking supplies and then sold the baked goods to others.

@kluurs said in Mildly interesting:

Thankfully, the President is emptying the prisons of white collar criminals - making more room for true felons such as this woman who purchased baking supplies and then sold the baked goods to others.

Hmm. I think I might need verification on that one.

-

Thankfully, the President is emptying the prisons of white collar criminals - making more room for true felons such as this woman who purchased baking supplies and then sold the baked goods to others.

@kluurs said in Mildly interesting:

Thankfully, the President is emptying the prisons of white collar criminals - making more room for true felons such as this woman who purchased baking supplies and then sold the baked goods to others.

Malicious prosecution sez I. There’s a difference between the letter and intent of a law. In any event I seriously doubt she’s going to see any jail time.

-

Picasso and his beloved Siamese cat Minou in the artist's studio at 11 Boulevard de Clichy, Montmartre, Paris, in December 1910

Today is the birthday of the genius Spanish artist Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso. Yes, it is Pablo Picasso's name quoted in his birth certificate

That's one hell of a name.

-

Picasso and his beloved Siamese cat Minou in the artist's studio at 11 Boulevard de Clichy, Montmartre, Paris, in December 1910

Today is the birthday of the genius Spanish artist Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso. Yes, it is Pablo Picasso's name quoted in his birth certificate

That's one hell of a name.

-

Thankfully, the President is emptying the prisons of white collar criminals - making more room for true felons such as this woman who purchased baking supplies and then sold the baked goods to others.

@kluurs said in Mildly interesting:

Thankfully, the President is emptying the prisons of white collar criminals - making more room for true felons such as this woman who purchased baking supplies and then sold the baked goods to others.

Why would Trump have anything to do with a a Michigan prosecution? This is a Michigan thing, and whatever Trump’s doing has absolutely nothing to do with it.

-

Apparently she was offered a plea where all she could just pay back the amount she had used to buy the ingredients, but she refused it.

-

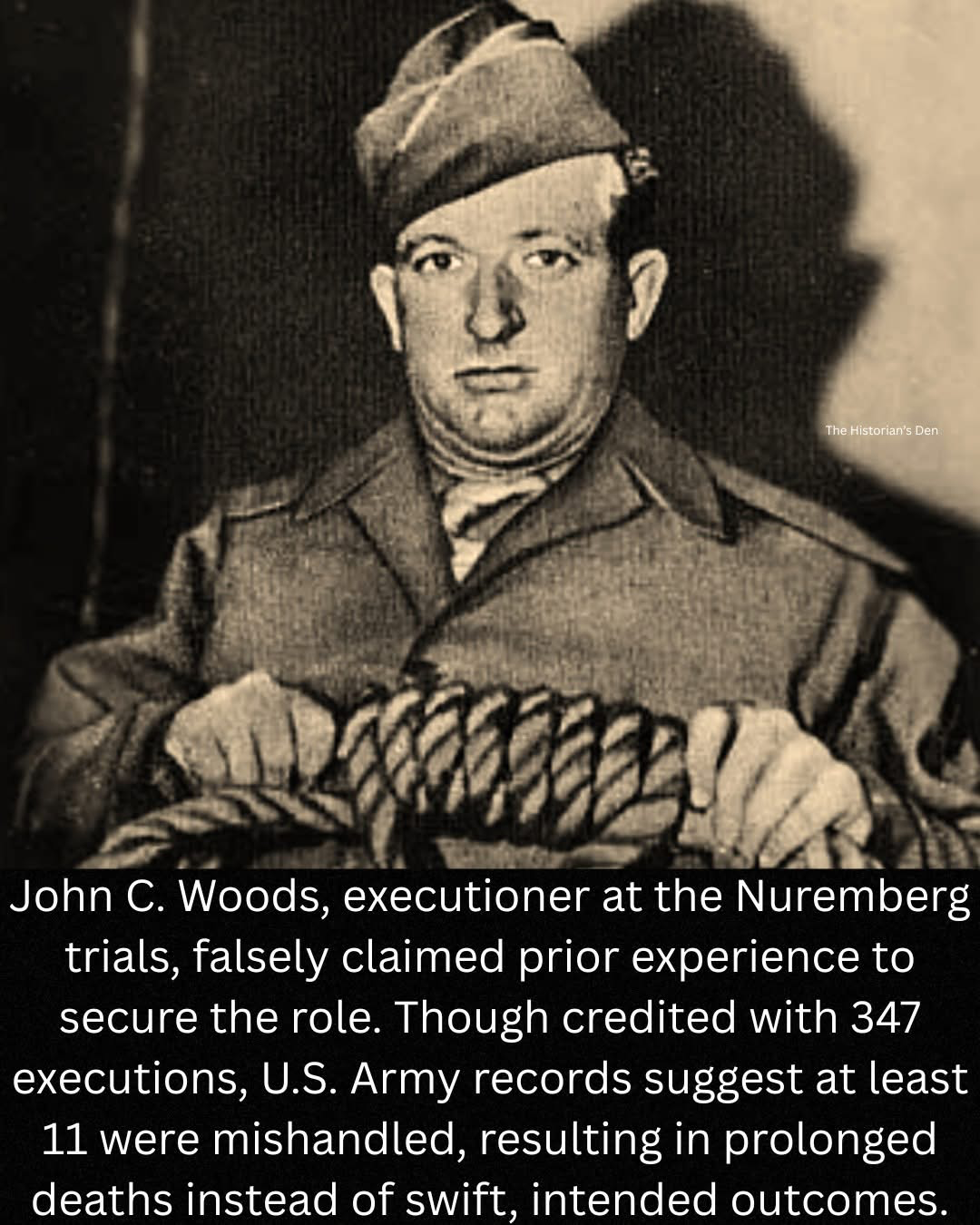

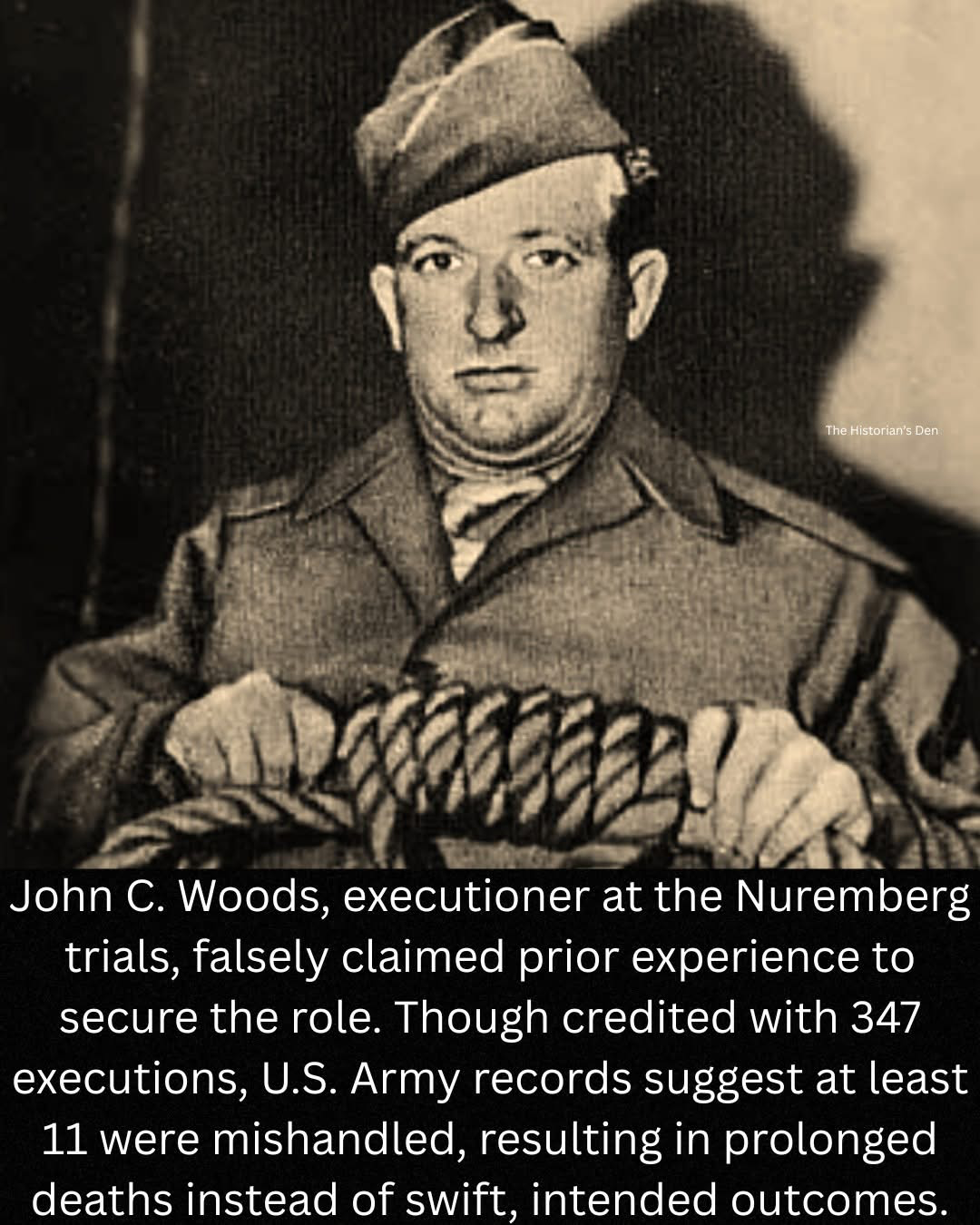

John C. Woods, the man who carried out the executions after the Nuremberg trials. You’d think someone in that role would be highly trained, right? Turns out, he wasn’t. He lied about being an assistant hangman to get the job. No one double-checked, and boom, he was in charge of one of the most high-profile justice operations in history.

He’s officially credited with 347 executions, but here’s the unsettling part: the U.S. Army later estimated that at least 11 of those were botched. Instead of a quick, clean break, some prisoners died slowly. It wasn’t just tragic, it was messy, and it cast a shadow over what was supposed to be a moment of moral reckoning.

And get this, Woods didn’t die in battle or fade into obscurity. He was electrocuted while working on a generator in Guam in 1950. A strange, almost ironic end for someone whose legacy is tangled in justice, deception, and a whole lot of uncomfortable questions. Makes you wonder how many other “experts” in history just… winged it.

#imposter #thehistoriansden

-

John C. Woods, the man who carried out the executions after the Nuremberg trials. You’d think someone in that role would be highly trained, right? Turns out, he wasn’t. He lied about being an assistant hangman to get the job. No one double-checked, and boom, he was in charge of one of the most high-profile justice operations in history.

He’s officially credited with 347 executions, but here’s the unsettling part: the U.S. Army later estimated that at least 11 of those were botched. Instead of a quick, clean break, some prisoners died slowly. It wasn’t just tragic, it was messy, and it cast a shadow over what was supposed to be a moment of moral reckoning.

And get this, Woods didn’t die in battle or fade into obscurity. He was electrocuted while working on a generator in Guam in 1950. A strange, almost ironic end for someone whose legacy is tangled in justice, deception, and a whole lot of uncomfortable questions. Makes you wonder how many other “experts” in history just… winged it.

#imposter #thehistoriansden

He’s officially credited with 347 executions, but here’s the unsettling part: the U.S. Army later estimated that at least 11 of those were botched. Instead of a quick, clean break, some prisoners died slowly.

Is that "failure rate" higher or lower than the failure rate of the average properly trained/certified professional hangperson?

-

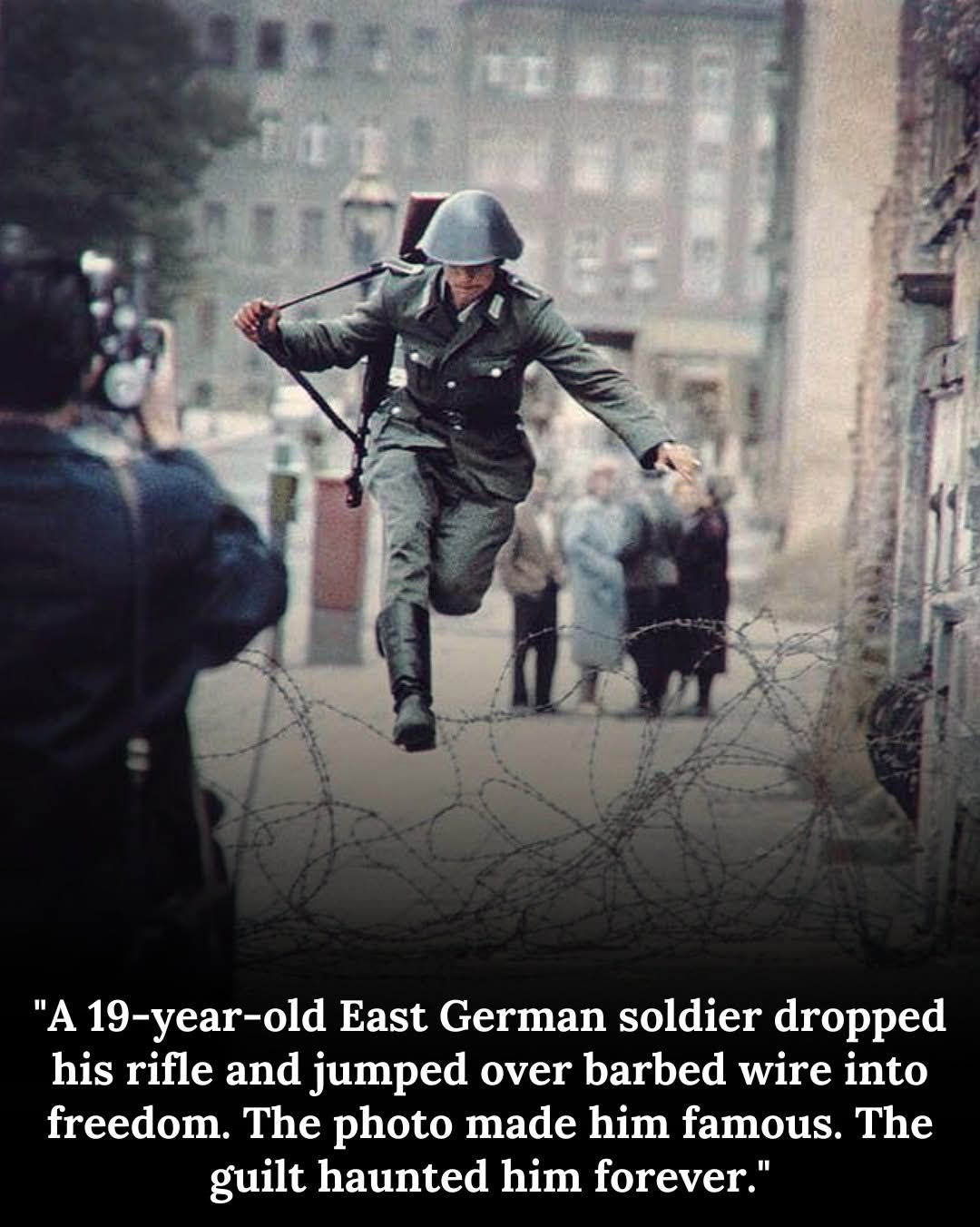

August 15, 1961. Just two days after construction on the Berlin Wall began, a 19-year-old East German soldier named Konrad Schumann stood guard at a barbed wire barrier on Bernauer Strasse.

His orders were simple: prevent anyone from crossing into West Berlin. Shoot if necessary.

But Konrad was looking at the wire and thinking about his own life on the other side of it.

He'd been conscripted into the East German border police just months earlier—a farm boy from Bavaria who never wanted to be a soldier, never wanted to patrol a border that split families and trapped an entire population. Now he stood in full uniform, rifle in hand, guarding a barrier that made him sick to look at.

West Berlin was right there. Thirty feet away. Freedom. Just thirty feet.

Behind him: East Germany, the Stasi, surveillance, restrictions on where you could go, what you could say, who you could become. A life of watching neighbors disappear in the night. A life of knowing that one wrong word could destroy your family.

In front of him: West Berlin. Possibility. Risk. The unknown.

Konrad watched West Berlin civilians gathering on the other side of the wire. They were calling to him. Encouraging him. A West German police van pulled up conspicuously close, its doors open—an obvious invitation.

His fellow guards were distracted, turned the other way.

This was the moment. Right now. If he waited, the wire would become concrete. The barrier would become a wall. This chance would never come again.

Konrad Schumann dropped his rifle.

He ran.

He jumped.

For a single frozen moment, he was suspended in mid-air over the barbed wire—one boot still in East Germany, one reaching toward West Berlin, his body arched in pure, desperate momentum.

A West German photographer named Peter Leibing captured that exact instant. The photograph is perfect in its symbolism: a young man literally leaping from oppression toward freedom, caught between two worlds, committed to the jump with no way back.

Konrad landed in West Berlin. The police van sped him away before East German guards could react. He was free.

The photograph circulated globally within hours. It became an instant icon of the Cold War—"The Leap to Freedom." Western media celebrated Konrad as a hero. A symbol of courage. Proof that people would risk everything to escape communism.

Konrad Schumann settled in Bavaria, West Germany. He worked quietly in an Audi factory for decades. He married, had children, and built a simple, normal life far from the cameras and the politics and the symbolism.

But he was never free of that jump.

The photograph haunted him. It made him famous in a way he never wanted. Everywhere he went, people recognized him. Journalists wanted interviews. Politicians wanted to use his story. He became a symbol when all he'd wanted was to be a person.

Worse, he felt guilty. Crushing, unrelenting guilt.

He'd left his family behind in East Germany. His parents. His siblings. After his escape, the Stasi harassed them relentlessly. They were interrogated, surveilled, punished for Konrad's betrayal. For years, he couldn't contact them. They became collateral damage for his freedom.

Konrad struggled with depression. He drank. The weight of being "The Man Who Jumped" crushed him in ways the wire never had.

In 1989, the Berlin Wall fell. Germany reunified. Konrad could finally return to his homeland, finally see his family again. It should have been a triumph—the vindication of his choice, proof that his leap had been on the right side of history.

But when Konrad returned to East Germany, he felt like a stranger. The village he'd grown up in had changed. His family had lived entire lives without him. The East Germans who'd stayed didn't see him as a hero—many saw him as a deserter, a traitor who'd abandoned his people and built a comfortable life in the West while they suffered.

He didn't belong in the East anymore. But he'd never fully belonged in the West either.

On June 20, 1998, Konrad Schumann hanged himself in an orchard near his home in Bavaria. He was 56 years old. He left no note, but friends said he'd been struggling for years with depression and the burden of his past.

The man who became a global symbol of freedom never found peace in the freedom he'd won.

His story forces brutal questions: What's the cost of becoming a symbol? Can you escape history even when you physically escape? Is freedom worth it if it destroys everyone you left behind?

Konrad's leap took three seconds. The photograph captured one perfect instant of courage and hope. But the aftermath lasted 37 years and ended in a tree with a rope.

That photograph still appears in history textbooks. It's still called "The Leap to Freedom." Students see it and think about courage, about the Cold War, about the triumph of the human spirit.

They rarely learn that the man in the photograph never escaped the jump. That he carried it with him every day. That the symbol of freedom died by his own hand, haunted by the choice that made him famous.

August 15, 1961: A 19-year-old East German soldier dropped his rifle and leaped over barbed wire into West Berlin. The photo made him a global symbol of freedom.

But his family was punished. His guilt never faded. When the wall finally fell, he still didn't belong anywhere.

In 1998, Konrad Schumann took his own life.

The man who symbolized freedom never found peace in it. -

"Three minutes from the moon, alarms screamed through the cabin—but one woman's code, written with less memory than a text message, made the split-second decision that saved them."

July 20, 1969. 240,000 miles from Earth.

Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin are descending toward the lunar surface in the Eagle lander. Millions watch on television. The entire world holds its breath.

Then, alarms start screaming.

1201. 1202. EXECUTIVE OVERFLOW.

The computer is dying. Overloaded. Failing at the worst possible moment.

Mission Control goes silent. Should they abort? Decades of work, billions of dollars, humanity's greatest dream—all threatened by a computer error three minutes from touchdown.

But the landing continues.

Because 240,000 miles away, back on Earth, a 33-year-old woman had already solved this problem.

Her name was Margaret Hamilton, and she had spent years writing the code that would either save these astronauts or doom them.

In 1969, Margaret Hamilton was doing something almost nobody understood: writing software that would navigate humans to another world.

She was the Director of the Software Engineering Division at MIT's Instrumentation Laboratory, leading the team responsible for the Apollo Guidance Computer—the onboard brain that would control a spacecraft traveling farther from home than any human had ever ventured.

The Apollo computer had 72 kilobytes of memory.

Let that sink in. A single photo on your phone today uses more memory than the entire computer system that landed humans on the moon. They were programming a machine less powerful than a modern calculator to perform one of the most complex tasks in human history.

And they were doing it with primitive tools—feeding punch cards into room-sized computers, one line of code at a time. No error messages that made sense. No "undo" button. No Google to search for answers.

Every single line had to be perfect.

Because out there, 240,000 miles from Earth, there was no tech support. No software update. No second chance.

If her code failed, three astronauts would die in the vacuum of space, and humanity's greatest dream would become its most public tragedy.

Hamilton understood something most engineers at NASA didn't grasp yet: software wasn't just a tool—it was the foundation everything else depended on.

While some colleagues dismissed programming as clerical work, something secondary to the "real" engineering of rockets and spacecraft, Hamilton insisted software deserved the same rigor, testing, and respect as any other discipline.

She demanded resilience. Error detection. Recovery systems that could handle the unexpected.

Some thought she was overthinking it. Overcomplicating things.

Margaret Hamilton knew better.

She built into her code something revolutionary: the ability to prioritize. To make decisions. To adapt when everything went wrong.

She programmed the computer to think: If I'm overwhelmed, what's essential for survival? What can wait? What must continue no matter what?

It seemed like paranoia.

Until July 20, 1969, when it became prophecy.

As Armstrong and Aldrin descended toward the Sea of Tranquility, the Eagle's rendezvous radar—which should have been turned off—was feeding unnecessary data into the computer. The system was being asked to do too much at once.

1201. Executive overflow.

The alarm meant: I'm drowning. I can't process everything. I might crash.

At Mission Control, controllers frantically checked their screens. The flight director demanded answers: Go or no-go?

Jack Garman, a 24-year-old guidance officer, remembered something from months of training. These alarms meant the computer was shedding non-essential tasks to focus on what mattered.

Hamilton's code was doing exactly what she'd designed it to do.

"We're go on that alarm," Garman said.

The landing continued.

The alarms kept blaring—1202, 1201, 1202—but Armstrong kept descending. The computer kept calculating. Hamilton's software kept prioritizing, adapting, surviving.

At 4:17 PM Eastern Time, Armstrong's voice crackled across 240,000 miles of space:

"The Eagle has landed."

Humanity had touched another world.

And it happened because one woman had anticipated the crisis, engineered resilience into every line of code, and refused to accept "good enough" when three lives hung in the balance.

The famous photograph captured it all: Margaret Hamilton standing next to a stack of printed code—her Apollo program—stacked taller than she was.

That tower of paper represented something invisible but essential. The hidden architecture that made the impossible possible.

After Apollo 11, the astronauts became legends. The rocket engineers got recognition. But the woman whose code guided them to the moon and back?

She was a footnote. Overlooked. Underestimated.

For 47 years.

In 2016, President Barack Obama finally awarded Margaret Hamilton the Presidential Medal of Freedom—the nation's highest civilian honor—acknowledging her contribution to one of humanity's greatest achievements.

But her legacy was already written in every line of code we depend on today.

Hamilton didn't just write software—she defined what software engineering could be. She proved it wasn't clerical work but a rigorous discipline requiring precision, creativity, and foresight. She coined the very term "software engineering" to give her field the respect it deserved.

Every app on your phone, every computer running hospitals and airplanes and power grids, every system that keeps modern civilization functioning—they all rest on the foundation Margaret Hamilton built.

She was 33 years old, working in a field that barely existed, solving problems no one had ever faced, with technology that seems laughable by today's standards.

And she did it so brilliantly that when alarms screamed and computers overloaded and everything seemed to be failing, her code made the split-second decisions that saved three lives and fulfilled humanity's greatest dream.

Margaret Hamilton didn't go to the moon.

But without her, no one would have.

And the next time you write a line of code, debug a program, or trust your life to software flying you across the country, remember:

Every system that thinks, adapts, and survives when things go wrong owes a debt to a woman who refused to let three astronauts die because of an oversight.

She taught computers to make the impossible possible.

One line of code at a time.