Mildly interesting

-

They called him "The Stupid"—and that's exactly what he wanted.

When Navy sailor Douglas Hegdahl was captured during the Vietnam War and thrown into the infamous Hanoi Hilton prison camp, he made a decision that would save hundreds of lives. He would play dumb.

Hegdahl acted confused, clumsy, harmless. His captors laughed at him. They gave him freedom to wander because they thought he was too simple to be a threat.

They were catastrophically wrong.

While pretending to stumble around, Hegdahl was secretly pouring dirt into enemy truck fuel tanks, quietly sabotaging their operations. But his greatest act of defiance was invisible: he began memorizing every detail about his fellow prisoners—names, capture dates, conditions—information the enemy deliberately kept hidden from the world.

256 names. 256 faces. 256 families who deserved to know their loved ones were alive.

How did he remember them all? He set the information to the tune of "Old MacDonald Had a Farm," singing it silently in his head, day after day.

In 1969, Hegdahl was released as part of a propaganda stunt. The North Vietnamese thought they were freeing a harmless fool.

Instead, they released one of the war's most valuable intelligence assets. The moment he reached American soil, Hegdahl delivered every name, every detail, ensuring that 256 prisoners would not be forgotten.

Sometimes the most powerful weapon isn't strength—it's the courage to let others underestimate you.

@Mik said in Mildly interesting:

They called him "The Stupid"—and that's exactly what he wanted...

Actually, during the Vietnam War there was a program to enlist low IQ people and send them into combat.

[McNamara's Morons](https://en.wikipedia.org › wiki › Project_100,000)

-

@jon-nyc said in Mildly interesting:

Among the statistical correlations with this are amusing oddities such as the phenotypes of the antifa sorts harassing ICE officers, and the phenotypes of the ICE officers. It's wealthier white kids harassing working class minorities.

Another amusing correlation that made its way around conservative media was the makeup of the No Kings protests. Lots of elderly white people.

-

Thankfully, the President is emptying the prisons of white collar criminals - making more room for true felons such as this woman who purchased baking supplies and then sold the baked goods to others.

@kluurs said in Mildly interesting:

Thankfully, the President is emptying the prisons of white collar criminals - making more room for true felons such as this woman who purchased baking supplies and then sold the baked goods to others.

Hmm. I think I might need verification on that one.

-

Thankfully, the President is emptying the prisons of white collar criminals - making more room for true felons such as this woman who purchased baking supplies and then sold the baked goods to others.

@kluurs said in Mildly interesting:

Thankfully, the President is emptying the prisons of white collar criminals - making more room for true felons such as this woman who purchased baking supplies and then sold the baked goods to others.

Malicious prosecution sez I. There’s a difference between the letter and intent of a law. In any event I seriously doubt she’s going to see any jail time.

-

Picasso and his beloved Siamese cat Minou in the artist's studio at 11 Boulevard de Clichy, Montmartre, Paris, in December 1910

Today is the birthday of the genius Spanish artist Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso. Yes, it is Pablo Picasso's name quoted in his birth certificate

That's one hell of a name.

-

Picasso and his beloved Siamese cat Minou in the artist's studio at 11 Boulevard de Clichy, Montmartre, Paris, in December 1910

Today is the birthday of the genius Spanish artist Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso. Yes, it is Pablo Picasso's name quoted in his birth certificate

That's one hell of a name.

-

Thankfully, the President is emptying the prisons of white collar criminals - making more room for true felons such as this woman who purchased baking supplies and then sold the baked goods to others.

@kluurs said in Mildly interesting:

Thankfully, the President is emptying the prisons of white collar criminals - making more room for true felons such as this woman who purchased baking supplies and then sold the baked goods to others.

Why would Trump have anything to do with a a Michigan prosecution? This is a Michigan thing, and whatever Trump’s doing has absolutely nothing to do with it.

-

Apparently she was offered a plea where all she could just pay back the amount she had used to buy the ingredients, but she refused it.

-

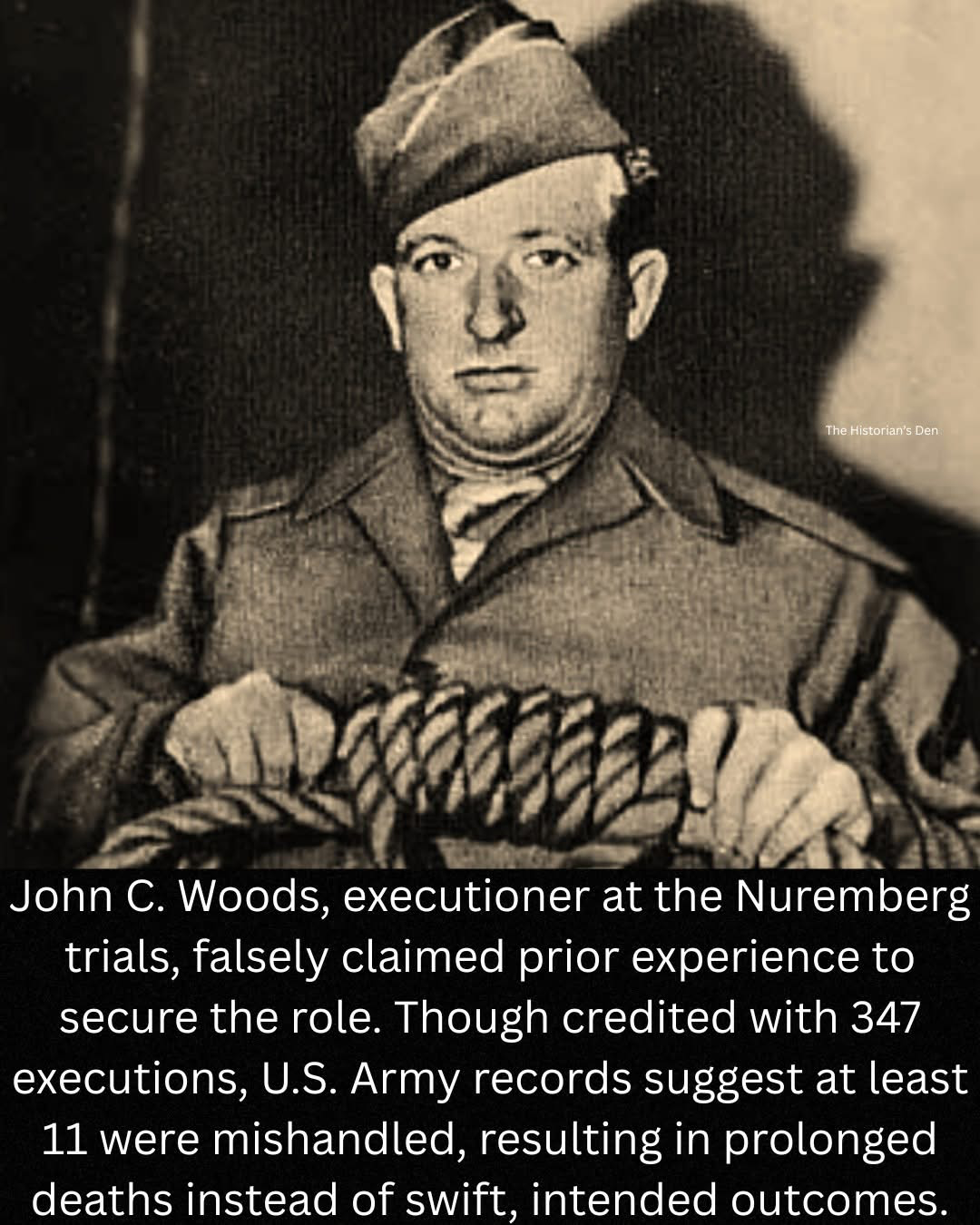

John C. Woods, the man who carried out the executions after the Nuremberg trials. You’d think someone in that role would be highly trained, right? Turns out, he wasn’t. He lied about being an assistant hangman to get the job. No one double-checked, and boom, he was in charge of one of the most high-profile justice operations in history.

He’s officially credited with 347 executions, but here’s the unsettling part: the U.S. Army later estimated that at least 11 of those were botched. Instead of a quick, clean break, some prisoners died slowly. It wasn’t just tragic, it was messy, and it cast a shadow over what was supposed to be a moment of moral reckoning.

And get this, Woods didn’t die in battle or fade into obscurity. He was electrocuted while working on a generator in Guam in 1950. A strange, almost ironic end for someone whose legacy is tangled in justice, deception, and a whole lot of uncomfortable questions. Makes you wonder how many other “experts” in history just… winged it.

#imposter #thehistoriansden

-

John C. Woods, the man who carried out the executions after the Nuremberg trials. You’d think someone in that role would be highly trained, right? Turns out, he wasn’t. He lied about being an assistant hangman to get the job. No one double-checked, and boom, he was in charge of one of the most high-profile justice operations in history.

He’s officially credited with 347 executions, but here’s the unsettling part: the U.S. Army later estimated that at least 11 of those were botched. Instead of a quick, clean break, some prisoners died slowly. It wasn’t just tragic, it was messy, and it cast a shadow over what was supposed to be a moment of moral reckoning.

And get this, Woods didn’t die in battle or fade into obscurity. He was electrocuted while working on a generator in Guam in 1950. A strange, almost ironic end for someone whose legacy is tangled in justice, deception, and a whole lot of uncomfortable questions. Makes you wonder how many other “experts” in history just… winged it.

#imposter #thehistoriansden

He’s officially credited with 347 executions, but here’s the unsettling part: the U.S. Army later estimated that at least 11 of those were botched. Instead of a quick, clean break, some prisoners died slowly.

Is that "failure rate" higher or lower than the failure rate of the average properly trained/certified professional hangperson?

-

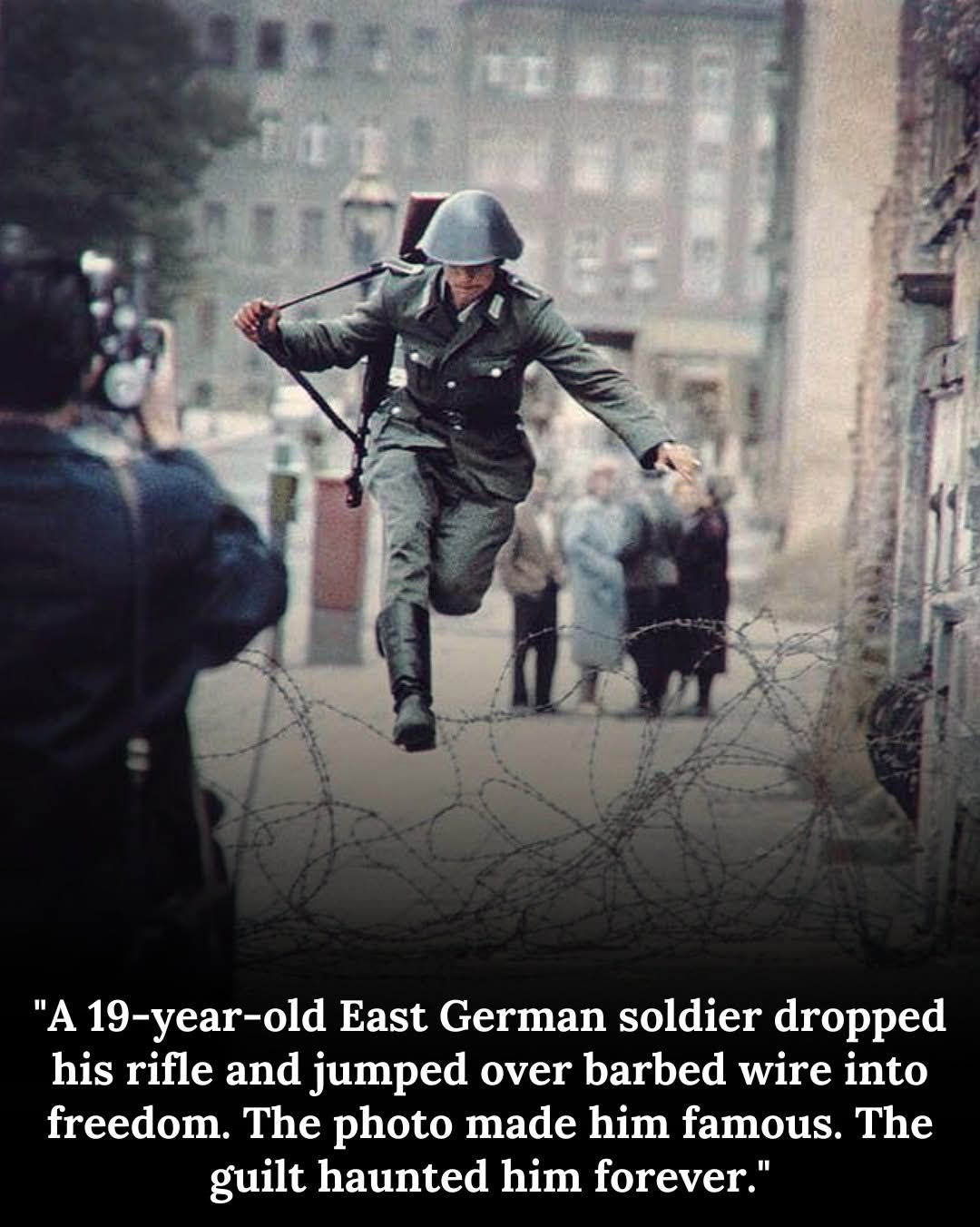

August 15, 1961. Just two days after construction on the Berlin Wall began, a 19-year-old East German soldier named Konrad Schumann stood guard at a barbed wire barrier on Bernauer Strasse.

His orders were simple: prevent anyone from crossing into West Berlin. Shoot if necessary.

But Konrad was looking at the wire and thinking about his own life on the other side of it.

He'd been conscripted into the East German border police just months earlier—a farm boy from Bavaria who never wanted to be a soldier, never wanted to patrol a border that split families and trapped an entire population. Now he stood in full uniform, rifle in hand, guarding a barrier that made him sick to look at.

West Berlin was right there. Thirty feet away. Freedom. Just thirty feet.

Behind him: East Germany, the Stasi, surveillance, restrictions on where you could go, what you could say, who you could become. A life of watching neighbors disappear in the night. A life of knowing that one wrong word could destroy your family.

In front of him: West Berlin. Possibility. Risk. The unknown.

Konrad watched West Berlin civilians gathering on the other side of the wire. They were calling to him. Encouraging him. A West German police van pulled up conspicuously close, its doors open—an obvious invitation.

His fellow guards were distracted, turned the other way.

This was the moment. Right now. If he waited, the wire would become concrete. The barrier would become a wall. This chance would never come again.

Konrad Schumann dropped his rifle.

He ran.

He jumped.

For a single frozen moment, he was suspended in mid-air over the barbed wire—one boot still in East Germany, one reaching toward West Berlin, his body arched in pure, desperate momentum.

A West German photographer named Peter Leibing captured that exact instant. The photograph is perfect in its symbolism: a young man literally leaping from oppression toward freedom, caught between two worlds, committed to the jump with no way back.

Konrad landed in West Berlin. The police van sped him away before East German guards could react. He was free.

The photograph circulated globally within hours. It became an instant icon of the Cold War—"The Leap to Freedom." Western media celebrated Konrad as a hero. A symbol of courage. Proof that people would risk everything to escape communism.

Konrad Schumann settled in Bavaria, West Germany. He worked quietly in an Audi factory for decades. He married, had children, and built a simple, normal life far from the cameras and the politics and the symbolism.

But he was never free of that jump.

The photograph haunted him. It made him famous in a way he never wanted. Everywhere he went, people recognized him. Journalists wanted interviews. Politicians wanted to use his story. He became a symbol when all he'd wanted was to be a person.

Worse, he felt guilty. Crushing, unrelenting guilt.

He'd left his family behind in East Germany. His parents. His siblings. After his escape, the Stasi harassed them relentlessly. They were interrogated, surveilled, punished for Konrad's betrayal. For years, he couldn't contact them. They became collateral damage for his freedom.

Konrad struggled with depression. He drank. The weight of being "The Man Who Jumped" crushed him in ways the wire never had.

In 1989, the Berlin Wall fell. Germany reunified. Konrad could finally return to his homeland, finally see his family again. It should have been a triumph—the vindication of his choice, proof that his leap had been on the right side of history.

But when Konrad returned to East Germany, he felt like a stranger. The village he'd grown up in had changed. His family had lived entire lives without him. The East Germans who'd stayed didn't see him as a hero—many saw him as a deserter, a traitor who'd abandoned his people and built a comfortable life in the West while they suffered.

He didn't belong in the East anymore. But he'd never fully belonged in the West either.

On June 20, 1998, Konrad Schumann hanged himself in an orchard near his home in Bavaria. He was 56 years old. He left no note, but friends said he'd been struggling for years with depression and the burden of his past.

The man who became a global symbol of freedom never found peace in the freedom he'd won.

His story forces brutal questions: What's the cost of becoming a symbol? Can you escape history even when you physically escape? Is freedom worth it if it destroys everyone you left behind?

Konrad's leap took three seconds. The photograph captured one perfect instant of courage and hope. But the aftermath lasted 37 years and ended in a tree with a rope.

That photograph still appears in history textbooks. It's still called "The Leap to Freedom." Students see it and think about courage, about the Cold War, about the triumph of the human spirit.

They rarely learn that the man in the photograph never escaped the jump. That he carried it with him every day. That the symbol of freedom died by his own hand, haunted by the choice that made him famous.

August 15, 1961: A 19-year-old East German soldier dropped his rifle and leaped over barbed wire into West Berlin. The photo made him a global symbol of freedom.

But his family was punished. His guilt never faded. When the wall finally fell, he still didn't belong anywhere.

In 1998, Konrad Schumann took his own life.

The man who symbolized freedom never found peace in it.