Mildly interesting

-

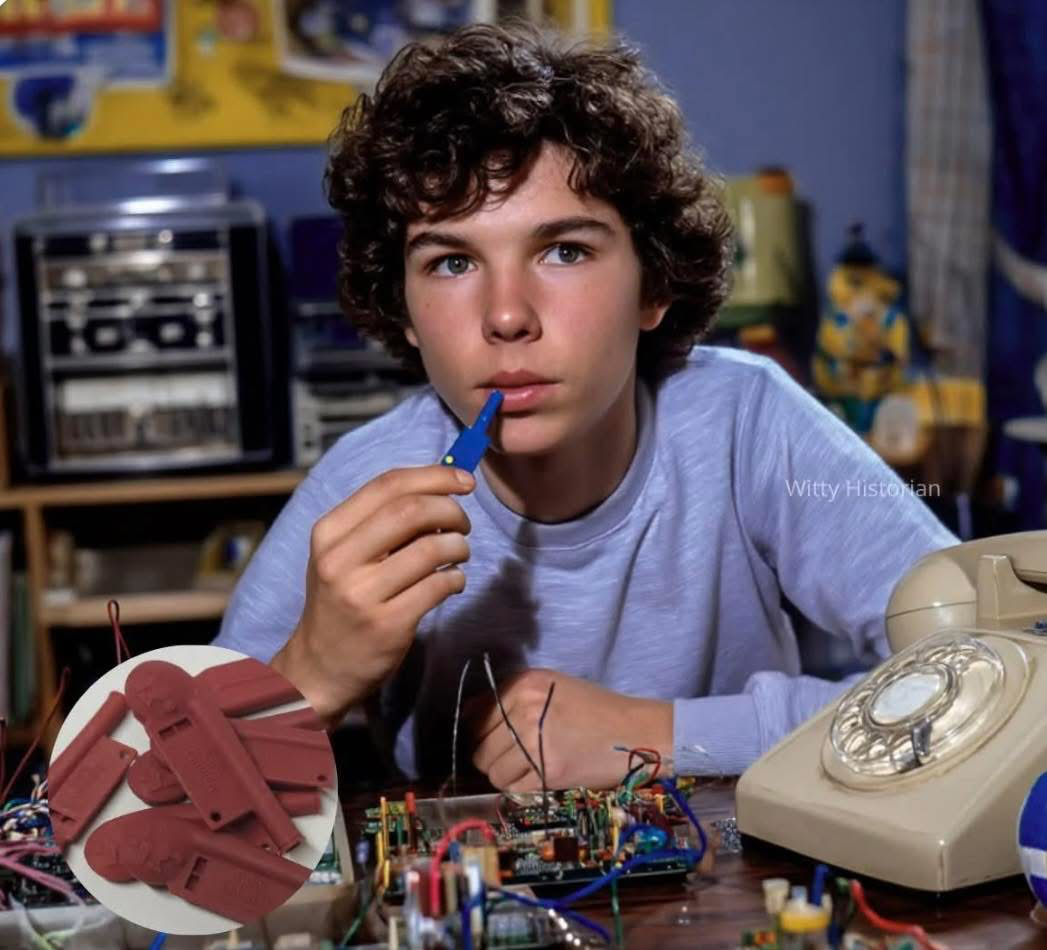

I thought it was cool that we figured out how to make free pay phone calls by tapping out the number on the receiver hook.

In the 1960s, a kid playing with a toy whistle from a Cap’n Crunch cereal made an odd discovery. The whistle produced a 2600-hertz tone, the same sound used by AT&T to control its phone network. That unlocked a loophole in the system, allowing them to hack into AT&T and get free long distance calls.

When pranksters and tech-savvy youth discovered this, they learned they could mimic the signal, tricking the network into granting free international calls. These early experimenters, dubbed “phone phreaks,” laid the groundwork for what would later become modern hacking culture.

The most famous of them, John Draper (nicknamed “Captain Crunch”) built electronic devices called “blue boxes” that reproduced the whistle’s tone with precision. Even a young Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak were captivated by the trick, selling their own blue boxes at college before founding Apple. What began as childlike curiosity revealed the fragility of the world’s largest communications system and marked the dawn of digital rebellion.

Added Fact: The 2600 Hz tone became so iconic that a hacker magazine, 2600: The Hacker Quarterly, was later named in its honor.

-

FDR always seemed like something of a grandfather figure. I just (re) learned that he was only 63 when he died.

That means when Pearl Harbor happened he was still in his 50s. And he was only 50 when first elected.

I’m sure I knew that back when that would have sounded much older to me.

-

-

@jon-nyc said in Mildly interesting:

Not saying this is easy, and I don’t know if this is what he did. If it were me attempting this, I think I would do it in a tip-toe manner, without letting the heels touch the ground.

-

“The classic example of a hijack is masturbation,” Edward Slingerland tells me. We’re talking about all the evolutionary quirks that humans tend to exploit — the cases where we’re “built” for one purpose, but decide to put that structure to other uses. And masturbation is a classic example.

In this week’s Mini Philosophy interview, I spoke with Slingerland about his book Drunk, in which he outlines his “intoxication thesis.” Slingerland argues it’s quite common to think that getting drunk is an evolutionary mistake. Some early Homo sapiens drank too much fermented fruit juice and discovered it was pretty fun. So they told their mates and, altogether, they clinked their frothy ciders and sang bawdy songs about hunting and gathering. But the human brain and body were not built to get drunk. Alcohol is effectively a poison. Our bodies don’t like it — or so the argument goes.

The intoxication thesis says this is all wrong. For Slingerland, drinking alcohol and getting drunk are important to human well-being and complex societies. It might not be what evolution “intended,” but it’s certainly given us a reproductive and interspecies advantage.

So, how is getting drunk different from other “evolutionary mistakes”? And what possible benefits might getting drunk give us? Today, we find out.

———

Read the full article: -

They called him "The Stupid"—and that's exactly what he wanted.

When Navy sailor Douglas Hegdahl was captured during the Vietnam War and thrown into the infamous Hanoi Hilton prison camp, he made a decision that would save hundreds of lives. He would play dumb.

Hegdahl acted confused, clumsy, harmless. His captors laughed at him. They gave him freedom to wander because they thought he was too simple to be a threat.

They were catastrophically wrong.

While pretending to stumble around, Hegdahl was secretly pouring dirt into enemy truck fuel tanks, quietly sabotaging their operations. But his greatest act of defiance was invisible: he began memorizing every detail about his fellow prisoners—names, capture dates, conditions—information the enemy deliberately kept hidden from the world.

256 names. 256 faces. 256 families who deserved to know their loved ones were alive.

How did he remember them all? He set the information to the tune of "Old MacDonald Had a Farm," singing it silently in his head, day after day.

In 1969, Hegdahl was released as part of a propaganda stunt. The North Vietnamese thought they were freeing a harmless fool.

Instead, they released one of the war's most valuable intelligence assets. The moment he reached American soil, Hegdahl delivered every name, every detail, ensuring that 256 prisoners would not be forgotten.

Sometimes the most powerful weapon isn't strength—it's the courage to let others underestimate you.