Mildly interesting

-

@kluurs I remember reading something similar about tardigrades (water bears). The US army actually had given a grant to scientists to study them. If I remember, it related to being able to re-hydrate blood, and possibly being able to use de-hydrated blood because of its easier to store and transport.

-

-

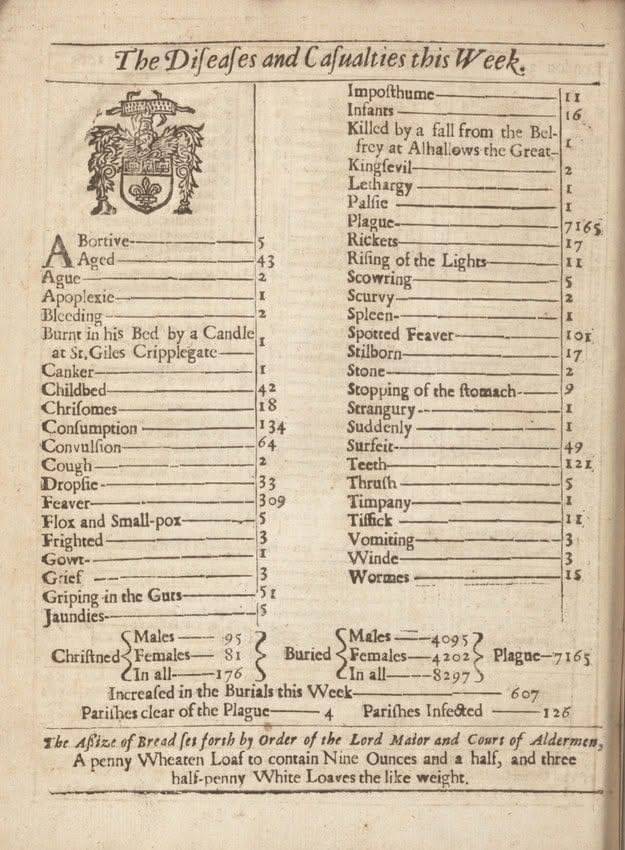

“Bill of mortality” from the Great Plague of London's deadliest week, which ended on this day in 1665, leaving a count of 7165 dead.

In addition to the high count attributed to "Plague" and other expected maladies of the time, we see deaths assigned to more enigmatic causes — “Frighted”, “Suddenly”, “Winde”, “Teeth”, and “Planet”. In addition to those that paint a very specific and vivid picture, e.g. “Burnt in his Bed by a Candle at St. Giles Cripplegate”.

More info, and the whole year of "bills" to view, here: https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/londons-dreadful-visitation-bills-of-mortality

-

Super photo(shop) of what it may have looked like when new; nonetheless true

https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/spain-uncovered-megalithic-monument/ -

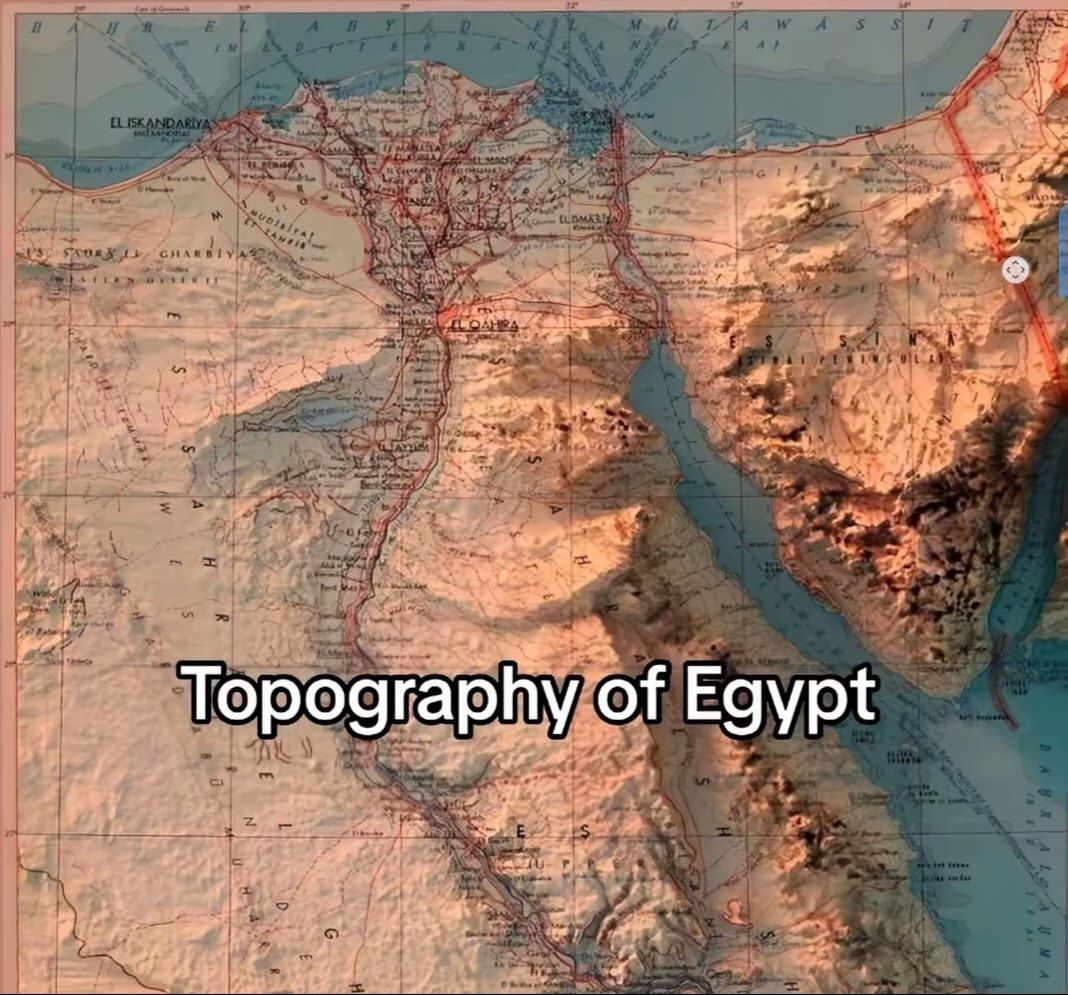

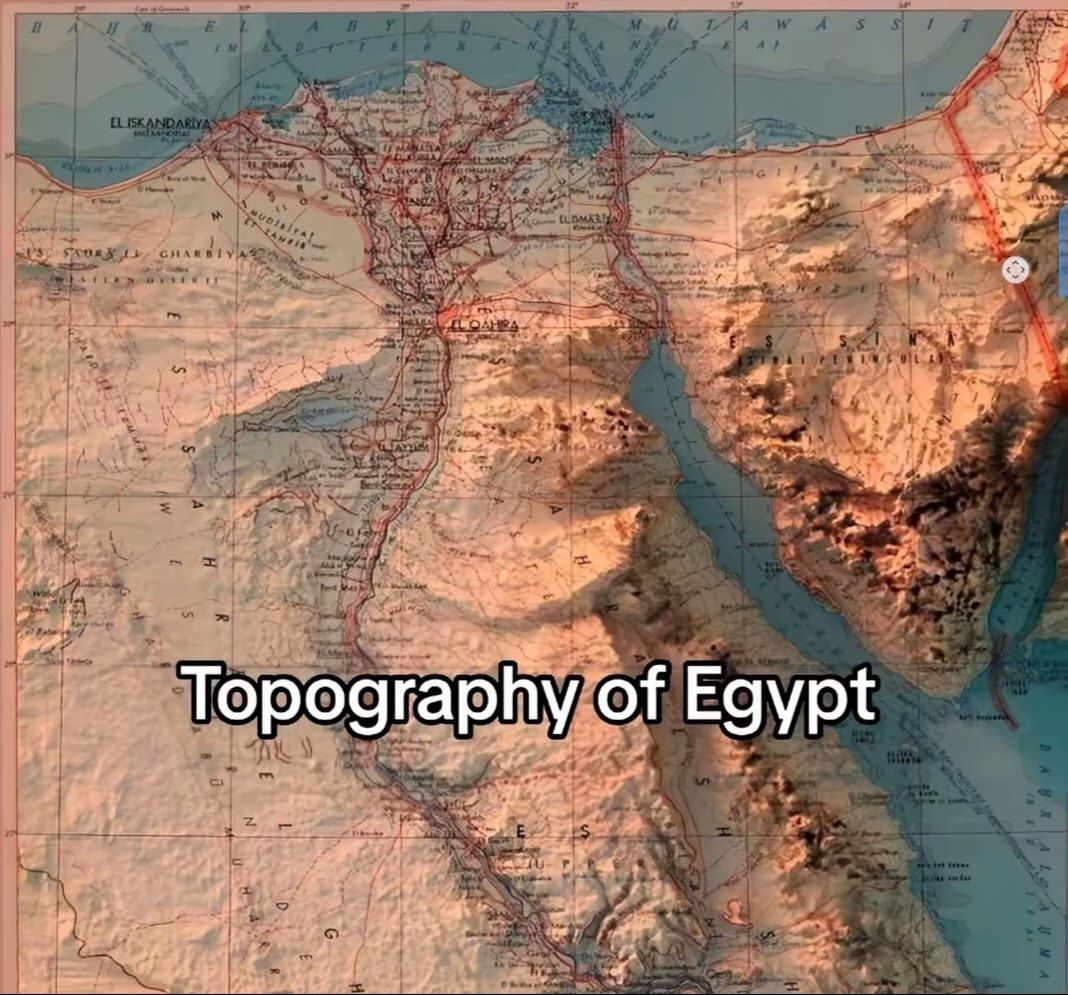

Can't recall seeing a relief map of this area; look at all those mountainous areas in Yemen etc!

@AndyD said in Mildly interesting:

Can't recall seeing a relief map of this area; look at all those mountainous areas in Yemen etc!

yemen is not on the map, thats over to the east across the red sea, maybe you are referring to the Sinai peninsula, which in the south is quite mountainous (eg...Mount Sinai)

-

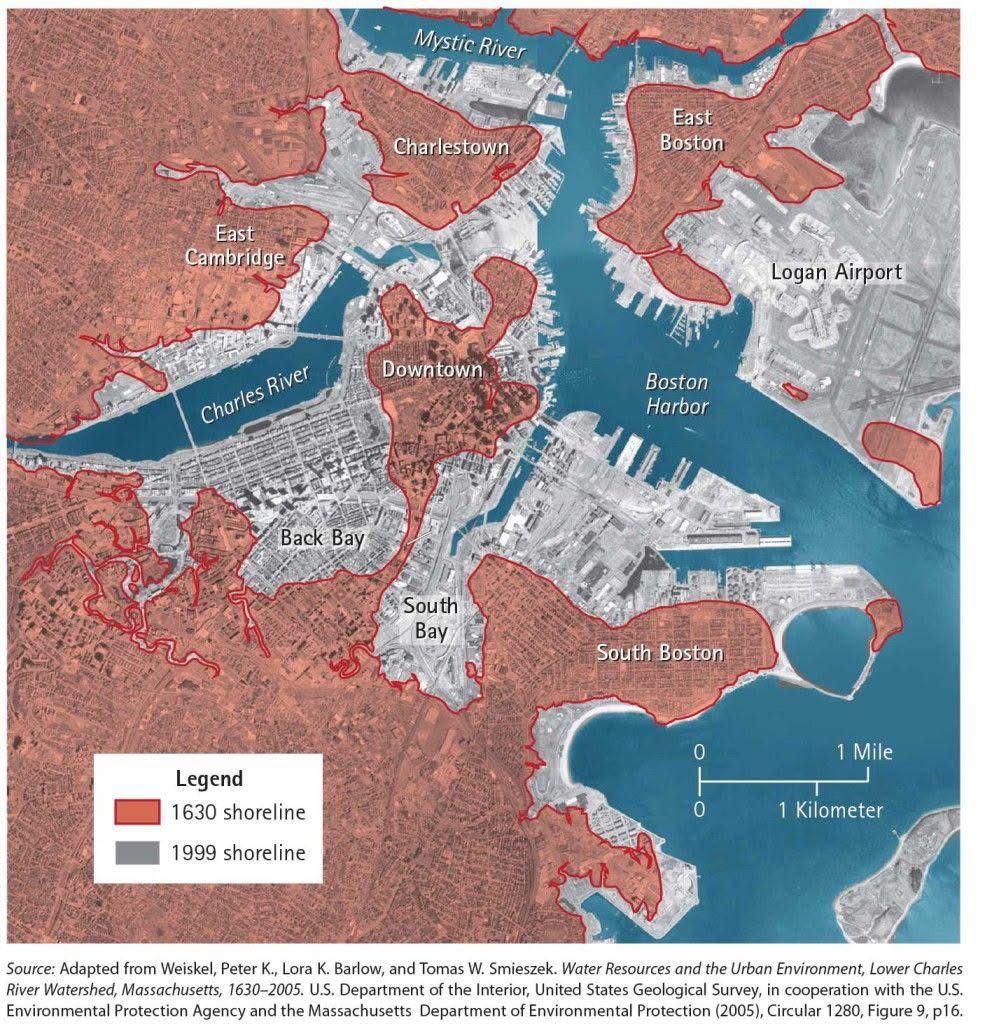

@jon-nyc Interesting. I would not have guessed that. I would have thought it was younger 100+ years ago.

-

This is interesting, if true. Complete opposite of what we learned from monopoly, which was to amass wealth and mercilessly crush your opponents. Of course we were like that with everything. All competition was blood sport.

The original Monopoly was invented by a woman in 1904 to highlight the dangers of unchecked capitalism, she was told her concept was too complex, then the idea was stolen.

Long before Monopoly became a family game-night staple, it was a pointed critique of economic inequality. The game was originally created in 1904 by Elizabeth Magie, an American writer, inventor, and staunch supporter of economist Henry George’s ideas about land reform. She called it The Landlord’s Game and designed it to demonstrate how wealth accumulation and rent-seeking concentrated power in the hands of a few while impoverishing everyone else.

Magie patented the game in 1904, including two rule sets: one where players competed to monopolize property and another where everyone benefited equally from shared wealth — a direct moral lesson about the difference between greed and fairness. She hoped it would teach players that monopolies harm society.

Years later, Charles Darrow encountered a version of Magie’s game, modified and circulating informally among friends and communities. He sold it to Parker Brothers in the 1930s, claiming it as his own invention. The company bought Magie’s patent for just $500 and erased her name from history. Monopoly went on to become one of the best-selling board games of all time — ironically celebrating the very capitalist spirit it was meant to criticize.

Added Fact: Elizabeth Magie’s original 1904 patent for The Landlord’s Game remains one of the earliest known board game patents filed by a woman in the United States.

-

There's a lesson here. I'd never heard this story.

𝗗𝗿. Frank Mayfield was touring the Tewksbury Institute when, on his way out, he accidentally bumped into an elderly floor maid. To ease the awkwardness, Dr. Mayfield struck up a conversation.

“How long have you worked here?” he asked.

“I’ve worked here almost since the place opened,” she replied.

“What can you tell me about the history of this place?”

“I don’t think I can tell you much,” she said, “but I can show you something.”

She led him down to the basement beneath the oldest wing of the building and pointed to a small, rusted cell. “That’s the cage where they used to keep Annie Sullivan,” she said.

“Who’s Annie?”

The maid explained that Annie was a young girl brought there because she was considered incorrigible—wild, uncontrollable, impossible to manage. She bit, screamed, and threw her food. Doctors and nurses couldn’t even examine her.

“I was just a few years younger than Annie,” the maid continued. “I used to think, ‘I’d hate to be locked in a cage like that.’ I wanted to help her, but if the doctors couldn’t, what could someone like me do?

“One night I baked some brownies after work. The next day, I set them on the floor outside her cage and said, ‘Annie, I baked these just for you. You can take them if you want.’ Then I hurried away, afraid she’d throw them. But she didn’t. She took the brownies and ate them. After that, she was a little nicer to me. Sometimes I’d talk to her, and once I even got her laughing.

“One of the nurses noticed and told the doctor. They asked if I’d help them with Annie. So whenever they needed to see her, I went in first to calm her, explain things, and hold her hand. That’s how they discovered Annie was nearly blind.”

After a year of slow, difficult progress, the Perkins Institute for the Blind opened. Annie was sent there, where she learned to read, write, and eventually became a teacher herself.

Years later, Annie returned to Tewksbury to visit and to help. The Director remembered a letter he had just received from a desperate father. His daughter was blind, deaf, and thought to be “deranged.” He didn’t want to put her in an asylum and asked if anyone might come work with her at home.

That is how Annie Sullivan became the lifelong companion and teacher of Helen Keller.

When Helen Keller later received the Nobel Prize, she was asked who had most influenced her life. She answered, “Annie Sullivan.”

But Annie replied, “No, Helen. The woman who influenced us both was a floor maid at Tewksbury who brought a little girl some brownies.”