Virtual learning ain't the same.

-

What would happen if Clinical Gross Anatomy became one more casualty of COVID-19? Dissections across the country were reformatted or suspended when lockdowns began in 2020, even as medical educations continued online. Physicians often consider the numerous hours spent in gross anatomy lab to be the most formative of their medical school careers. They transcend the cutting of flesh under the stench of formaldehyde. It’s about learning how to treat someone’s body with respect, work in a team, deal with death. “The anatomy lab is part of the gelling of camaraderie and team-building and peer-to-peer teaching. It’s a rite of passage,” says David Morton, an anatomist at the University of Utah School of Medicine.

Medical education—particularly Clinical Gross Anatomy—offers a window into what is lost when we lose in-person learning. The pandemic has forced medical schools to re-examine this 259-year-old tradition in the training of American physicians with approaches ranging from limited, socially distanced cadaver-cutting to replacing the entire experience with virtual reality programs. Ultimately, the switch to virtual learning across all areas of education asks us to reflect on the role that physical space and tactility play in our ability to process new information. For medicine in particular, the pandemic has brought debate over the digitalization of anatomical teaching to a head. Streamlining medical education could undermine the knowledge and skills—both scientific and humanistic—physicians are expected to have.

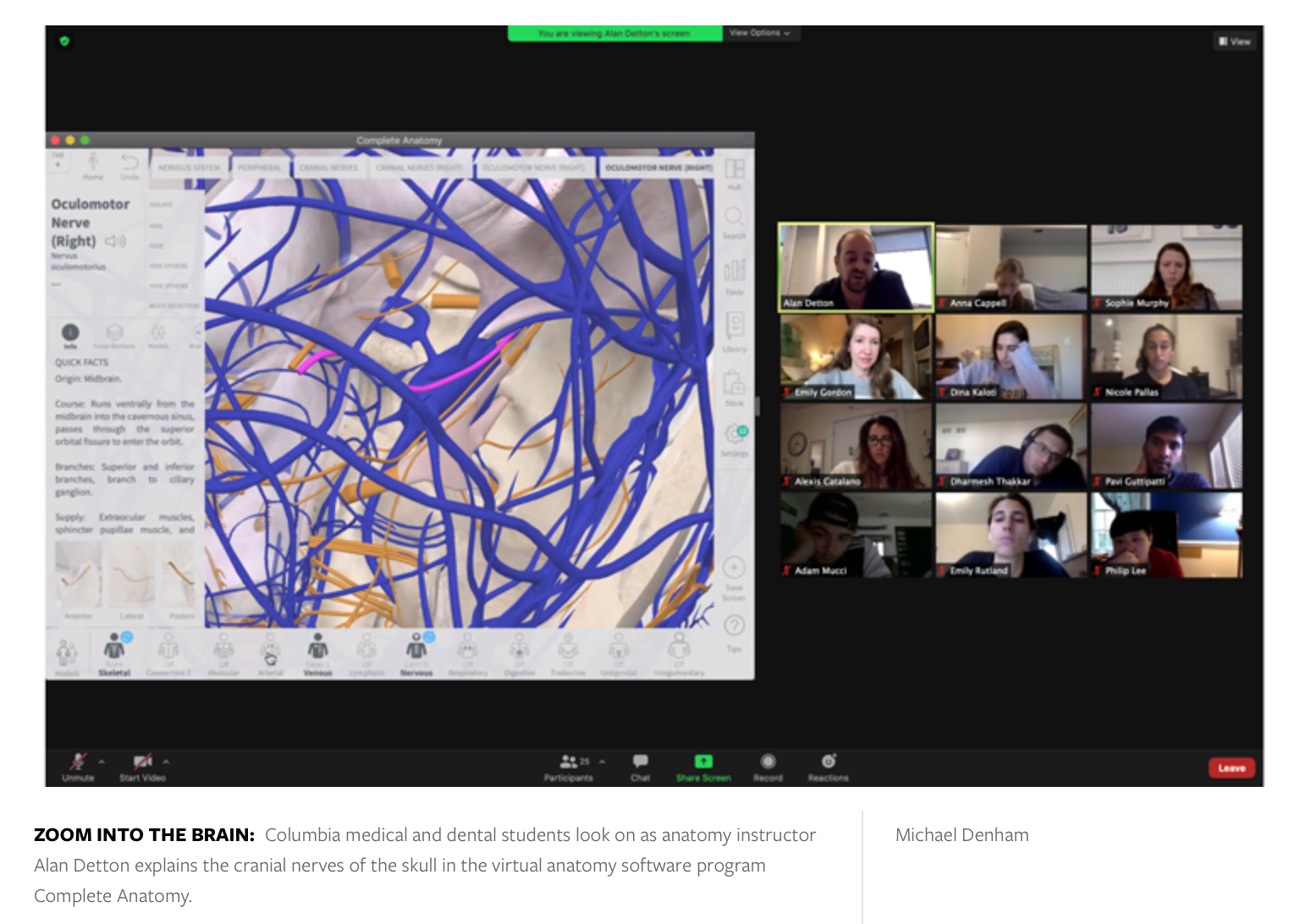

Alan Detton, an anatomy lecturer at Columbia, led a small group session of 24 students over Zoom. He offered playful mnemonics for remembering long lists of structures while guiding students through the complementary systems responsible for the functioning of the human brain on a three-dimensional model in Complete Anatomy, a virtual anatomy software program.

Even with the program’s abilities to highlight structures and hide or reveal layers of various organ systems, finding a cranial nerve amid branches of the internal carotid artery, venous sinuses in the brain’s protective covering, and connective tissue is often like looking at a bowl of spaghetti with the goal of finding a specific strand of pasta.

When I used the program a year before to learn anatomy, it was as a complement to my time in anatomy lab, a virtual guide to the real body before me. The physical body is messier, but it’s also easier to manipulate. Even if many of the nerves and blood vessels in the real body present as eerily similar gray strings, I could dig around, pin things back, explore their depth. Perception is lost without that physicality.

Neha Malhotra is a first-year medical student at the University of Toronto in a unique position to understand the changes this year in gross anatomy. She began her medical school career in the fall of 2019. But because she decided midway through her anatomy course to defer her studies for an extra year to spend time with family, she also experienced “virtual anatomy” in 2020. Learning online, she tells me, is no substitute for the real thing, even though the real thing is exhausting.

“It would be six hours of standing in a lab, a lot of content, dissecting, while also trying to learn and test each other,” Malhotra says. “It didn’t leave a lot of room for absorbing the material. But being in the anatomy lab and embodying that role of a medical student learning anatomy on a deceased body does make you feel like you’re going to be a doctor.”

-

Definitely face to face is better, even if the other face is a dead one. Lol

I have always been a big believer in that. I remember a “communications seminar” I took once. They said you should always try and move up one level.

If your task requires you to:

Send a letter —> send an email

Send an email —> telephone

Telephone —> video call

Video call —> meet in person

Obviously, every case is somewhat different, but the idea is to try and increase the level of human interaction.

I have flown across the ocean for a two hour meeting., Spending two days of travel there and back.

Not sure that will happen in the future, but I (and my boss) thought it was important.

-

Beyond some fairly basic levels, some skills really need to the taught/learnt hands-on in person.

Playing an instrument is like that.

Martial arts are like that.

Most sports are like that.

So are performing surgeries and doing dissections.@axtremus said in Virtual learning ain't the same.:

Beyond some fairly basic levels, some skills really need to the taught/learnt hands-on in person.

Playing an instrument is like that.

Martial arts are like that.

Most sports are like that.

So are performing surgeries and doing dissections.Ax, why do you think performing surgeries needs to be learned in-person?

-

@axtremus said in Virtual learning ain't the same.:

Beyond some fairly basic levels, some skills really need to the taught/learnt hands-on in person.

Playing an instrument is like that.

Martial arts are like that.

Most sports are like that.

So are performing surgeries and doing dissections.Ax, why do you think performing surgeries needs to be learned in-person?

@aqua-letifer said in Virtual learning ain't the same.:

Ax, why do you think performing surgeries needs to be learned in-person?

Performing surgery is a three dimensional activity where tactile feel is a vital aspect of that activity. Current simulation technology is still inadequate to simulate three dimensional objects with tactile feedback.

-

@aqua-letifer said in Virtual learning ain't the same.:

Ax, why do you think performing surgeries needs to be learned in-person?

Performing surgery is a three dimensional activity where tactile feel is a vital aspect of that activity. Current simulation technology is still inadequate to simulate three dimensional objects with tactile feedback.

@axtremus said in Virtual learning ain't the same.:

@aqua-letifer said in Virtual learning ain't the same.:

Ax, why do you think performing surgeries needs to be learned in-person?

Performing surgery is a three dimensional activity where tactile feel is a vital aspect of that activity. Current simulation technology is still inadequate to simulate three dimensional objects with tactile feedback.

Fascinating!