In the OR...

-

@mik said in In the OR...:

Pay has naught to do with it. It’s about the situations they deal with day in and day out.

Indirectly, I was trying to see if “the situations they deal with day in and day out” correlates to higher pay compared to other situations other nurses deal with day in and day out. It seems so far the answer is “no.”

-

@friday said in In the OR...:

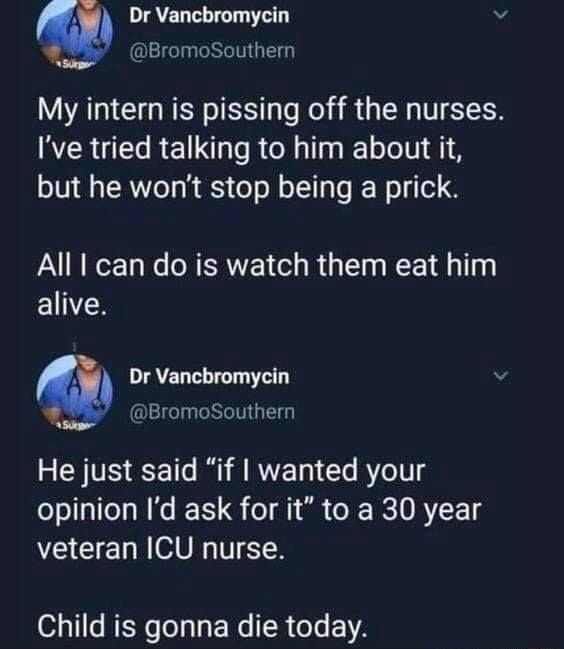

Out of curiosity, what would the nurses do to the intern?

Experience.

In the case of floor nurses, that's not too much the case. But in situations where decision making can be critical, the voice of experience can help an intern (or other trainee) make the right choice.

(By the way, they're not called "interns" anymore. It's PGY1 - Post Graduate Year One - trainee)

For example, it's the middle of the night, and something looks fishy in the ICU. Nurse calls the intern, who comes and looks at the patient and scratches his head. He doesn't want to wake the resident (PGY2-3), because the problem is probably simple and he'll get chewed out for waking the resident for something stupid, so he says to the nurse, "I dunno, what do you think?"

ICU nurse with 12 years' experience says, "Probably this, but it could be..."

It's part of the learning process, gleaning information from those who have been there and done that.

Though the nurse has no real authority, she can help guide decision making. If she thinks the intern's about to do something really stupid, she'll call the resident and say, "Um, Eddie's on call, and he's going to kill the patient in bed 5. Wanna come take a look?"

The same goes for the Emergency Room, esp if it's a busy one.

An anecdote:

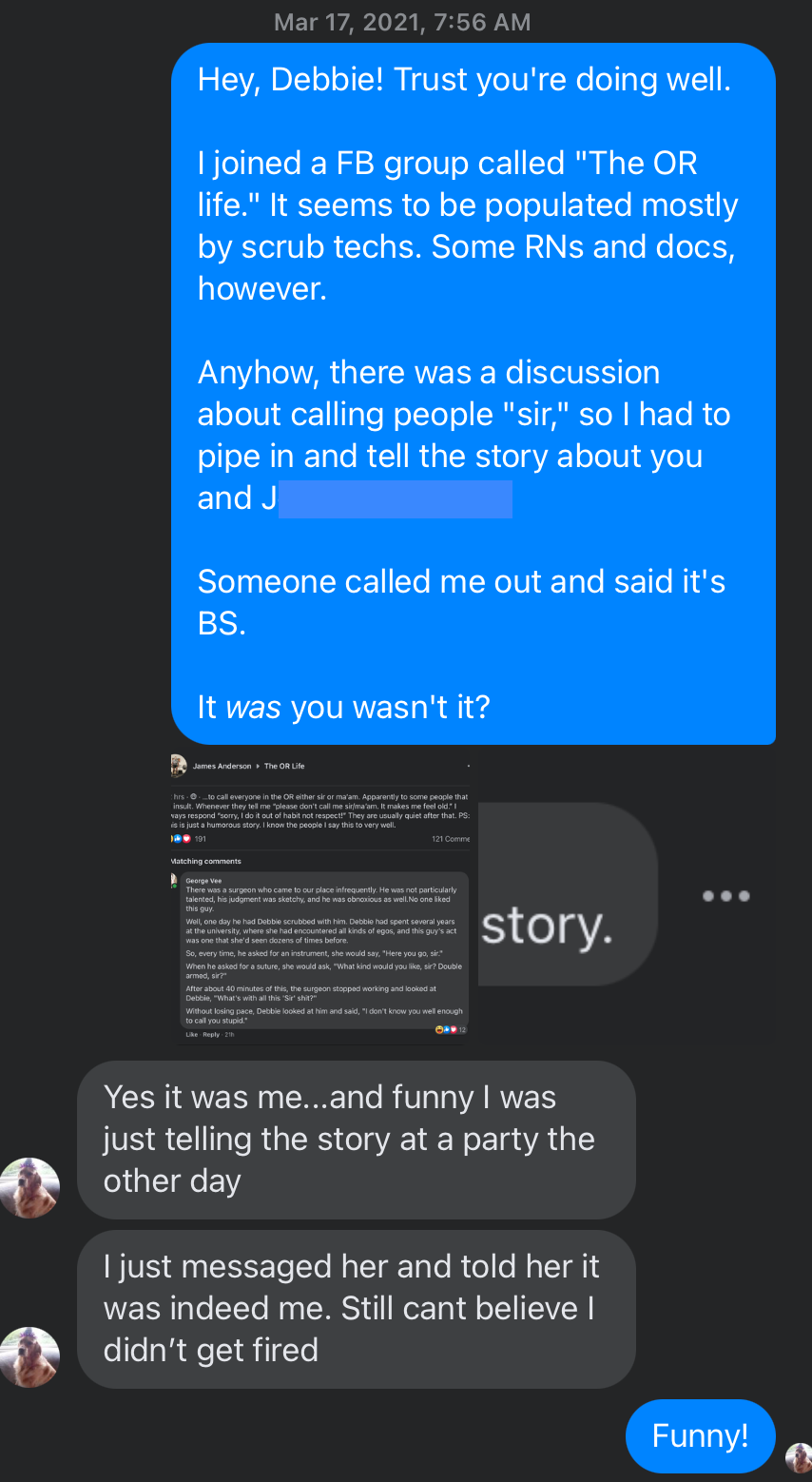

There was a surgeon who came to our place infrequently. He was not particularly talented, his judgment was sketchy, and he was obnoxious as well. No one liked this guy.

Well, one day he had Debbie scrubbed with him. Debbie had spent several years at the university, where she had encountered all kinds of egos, and this guy's act was one that she'd seen dozens of times before.

So, every time, he asked for an instrument, she would say, "Here you go, sir."

When he asked for a suture, she would ask, "What kind would you like, sir? Double armed, sir?"

After about 40 minutes of this, the surgeon stopped working and looked at Debbie, "What's with all this 'Sir' shit?"

Without losing pace, Debbie looked at him and said, "I don't know you well enough to call you stupid."

-

@friday said in In the OR...:

Out of curiosity, what would the nurses do to the intern?

Experience.

In the case of floor nurses, that's not too much the case. But in situations where decision making can be critical, the voice of experience can help an intern (or other trainee) make the right choice.

(By the way, they're not called "interns" anymore. It's PGY1 - Post Graduate Year One - trainee)

For example, it's the middle of the night, and something looks fishy in the ICU. Nurse calls the intern, who comes and looks at the patient and scratches his head. He doesn't want to wake the resident (PGY2-3), because the problem is probably simple and he'll get chewed out for waking the resident for something stupid, so he says to the nurse, "I dunno, what do you think?"

ICU nurse with 12 years' experience says, "Probably this, but it could be..."

It's part of the learning process, gleaning information from those who have been there and done that.

Though the nurse has no real authority, she can help guide decision making. If she thinks the intern's about to do something really stupid, she'll call the resident and say, "Um, Eddie's on call, and he's going to kill the patient in bed 5. Wanna come take a look?"

The same goes for the Emergency Room, esp if it's a busy one.

An anecdote:

There was a surgeon who came to our place infrequently. He was not particularly talented, his judgment was sketchy, and he was obnoxious as well. No one liked this guy.

Well, one day he had Debbie scrubbed with him. Debbie had spent several years at the university, where she had encountered all kinds of egos, and this guy's act was one that she'd seen dozens of times before.

So, every time, he asked for an instrument, she would say, "Here you go, sir."

When he asked for a suture, she would ask, "What kind would you like, sir? Double armed, sir?"

After about 40 minutes of this, the surgeon stopped working and looked at Debbie, "What's with all this 'Sir' shit?"

Without losing pace, Debbie looked at him and said, "I don't know you well enough to call you stupid."

@george-k said in In the OR...:

@friday said in In the OR...:

Out of curiosity, what would the nurses do to the intern?

Experience.

In the case of floor nurses, that's not too much the case. But in situations where decision making can be critical, the voice of experience can help an intern (or other trainee) make the right choice.

(By the way, they're not called "interns" anymore. It's PGY1 - Post Graduate Year One - trainee)

For example, it's the middle of the night, and something looks fishy in the ICU. Nurse calls the intern, who comes and looks at the patient and scratches his head. He doesn't want to wake the resident (PGY2-3), because the problem is probably simple and he'll get chewed out for waking the resident for something stupid, so he says to the nurse, "I dunno, what do you think?"

ICU nurse with 12 years' experience says, "Probably this, but it could be..."

It's part of the learning process, gleaning information from those who have been there and done that.

Though the nurse has no real authority, she can help guide decision making. If she thinks the intern's about to do something really stupid, she'll call the resident and say, "Um, Eddie's on call, and he's going to kill the patient in bed 5. Wanna come take a look?"

The same goes for the Emergency Room, esp if it's a busy one.

An anecdote:

There was a surgeon who came to our place infrequently. He was not particularly talented, his judgment was sketchy, and he was obnoxious as well. No one liked this guy.

Well, one day he had Debbie scrubbed with him. Debbie had spent several years at the university, where she had encountered all kinds of egos, and this guy's act was one that she'd seen dozens of times before.

So, every time, he asked for an instrument, she would say, "Here you go, sir."

When he asked for a suture, she would ask, "What kind would you like, sir? Double armed, sir?"

After about 40 minutes of this, the surgeon stopped working and looked at Debbie, "What's with all this 'Sir' shit?"

Without losing pace, Debbie looked at him and said, "I don't know you well enough to call you stupid."

I've seen ER nurses start an IV or procedure, then tell the resident to write the orders.

-

@george-k said in In the OR...:

@friday said in In the OR...:

Out of curiosity, what would the nurses do to the intern?

Experience.

In the case of floor nurses, that's not too much the case. But in situations where decision making can be critical, the voice of experience can help an intern (or other trainee) make the right choice.

(By the way, they're not called "interns" anymore. It's PGY1 - Post Graduate Year One - trainee)

For example, it's the middle of the night, and something looks fishy in the ICU. Nurse calls the intern, who comes and looks at the patient and scratches his head. He doesn't want to wake the resident (PGY2-3), because the problem is probably simple and he'll get chewed out for waking the resident for something stupid, so he says to the nurse, "I dunno, what do you think?"

ICU nurse with 12 years' experience says, "Probably this, but it could be..."

It's part of the learning process, gleaning information from those who have been there and done that.

Though the nurse has no real authority, she can help guide decision making. If she thinks the intern's about to do something really stupid, she'll call the resident and say, "Um, Eddie's on call, and he's going to kill the patient in bed 5. Wanna come take a look?"

The same goes for the Emergency Room, esp if it's a busy one.

An anecdote:

There was a surgeon who came to our place infrequently. He was not particularly talented, his judgment was sketchy, and he was obnoxious as well. No one liked this guy.

Well, one day he had Debbie scrubbed with him. Debbie had spent several years at the university, where she had encountered all kinds of egos, and this guy's act was one that she'd seen dozens of times before.

So, every time, he asked for an instrument, she would say, "Here you go, sir."

When he asked for a suture, she would ask, "What kind would you like, sir? Double armed, sir?"

After about 40 minutes of this, the surgeon stopped working and looked at Debbie, "What's with all this 'Sir' shit?"

Without losing pace, Debbie looked at him and said, "I don't know you well enough to call you stupid."

I've seen ER nurses start an IV or procedure, then tell the resident to write the orders.

-

When we installed EPIC, the docs had to order their labwork.

The trainwreck was massive and impressive to behold.

-

In my dotage, I'm waxing nostalgic. So, let me tell you about Art.

Art was a heart surgeon at the university. He graduated from medical school in 1946, and and did his training at the university where he joined the faculty. Art was the first surgeon in Chicago to use the heart-lung machine (I think in 1958?). Art never got board certified, but that didn't stop him from becoming chairman of cardiothoracic surgery at the U.

He was a uncompromising, demanding, supremely competent, and confident, surgeon. He brooked no nonsense, tolerated no idiocy or incompetence on anyone's part, though, during "easier" parts of the operation, there was some smalltalk to be had. He could do valve replacements like no one else. He never learned to do bypasses. For those operations, he'd open the chest, put the patient on bypass, and one of his partners would sew the vein grafts. Then, Art would take over and finish the case, weaning the patient from the pump, and closing.

He had a nurse that worked with him most of the time. Her name was Clara. She said she was from Switzerland, but because of her thick German accent, we all suspected "Switzerland" was a euphemism. At least we joked about it.

One day, in the early 80's, I was doing an aortic valve replacement with Art. I got the patient off to sleep, put in the jugular and arterial lines, and were off. Art scrubbed while I was doing this, and he came in, and Clara gowned and gloved him. He walked up to the table, on the patient's right, and put out his hand. Clara handed him a knife. He made the skin incision, put the knife down. Clara picked up the knife, and Art had his hand extended again. Clara handed him the cautery. He worked his way down to the sternum, and put the cautery down, and extended his hand. Clara handed him a clamp which he used to free up the tissues at the top of the sternum. Putting the clamp down, Clara handed him the sternal saw. He sawed through the sternum, put the saw down, and Clara handed him the cautery again to control whatever bleeding happened from the sternotomy. Then he put his hand out again, and Clara handed him a needle holder, armed with a suture. He put a circle of sutures in the ascending aorta and Clara handed him a knife. He made an incision, about ¼" long in the aorta, plugging it with his left index finger to stop the bleeding. He extended his right hand, and Clara handed him the aortic cannula, which he inserted and cinched down with the aforementioned suture.

Getting the picture?

OK, here's the amazing part. The first words Art said during this case (other than "good morning, George") were to me: "Give the heparin."

About 30 minutes of surgery, complex surgery, without a word being spoken.

Neat stuff.

Art died at the age of 90, in 2007. He was a remarkable man.

Addendum: One day, we had finished an aortic valve, and the team was closing up. I was in the ante-room of the OR, having a cup of coffee while my resident was taking care of the patient as they closed. Art came in, and sat next to me, also drinking a cup of coffee.

"Jesus, Art, that was amazing."

"What?"

"That aortic valve replacement took about 2 ½ hours. I've seen knee arthroscopies take longer than that!"

"Well, George, the knee is a very complicated structure."

-

Great stories!!!