About that "convalescent plasma."

-

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/24/health/fda-blood-plasma.html

Dr. Stephen M. Hahn, the commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, said 35 out of 100 Covid-19 patients “would have been saved because of the administration of plasma.”

But scientists were taken aback by the way the administration framed this data, which appeared to have been calculated based on a small subgroup of hospitalized Covid-19 patients in a Mayo Clinic study: those who were under 80 years old, not on ventilators and received plasma known to contain high levels of virus-fighting antibodies within three days of diagnosis.

What’s more, many experts — including a scientist who worked on the Mayo Clinic study — were bewildered about where the statistic came from. The number was not mentioned in the official authorization letter issued by the agency, nor was it in a 17-page memo written by F.D.A. scientists. It was not in an analysis conducted by the Mayo Clinic that has been frequently cited by the administration.

“For the first time ever, I feel like official people in communications and people at the F.D.A. grossly misrepresented data about a therapy,” said Dr. Walid Gellad, who leads the Center for Pharmaceutical Policy and Prescribing at the University of Pittsburgh.It is especially worrisome, he said, given concerns over how Mr. Trump has appeared to politicize the process of approving treatments and vaccines for the coronavirus. Over the next couple of months, as data emerges from vaccine clinical trials, the safety of potentially millions of people will rely on the scientific judgment of the F.D.A. “That’s a problem if they’re starting to exaggerate data,” Dr. Gellad said. “That’s the big problem.”

When asked where the 35 percent figure came from, an agency spokeswoman initially directed a reporter to a graph of survival statistics buried in the Trump administration’s application for emergency authorization. The chart, analyzing the same tiny subset of Mayo Clinic study patients, did not include numerical figures, but it appeared to indicate a 30-day survival probability of about 63 percent in patients who received plasma with a low level of antibodies, compared with about 76 percent in those who received a high level of antibodies.

On Monday, Dr. Peter Marks, the director of F.D.A.’s center for biologics, evaluation and research, said that the agency reviewed published studies of plasma and conducted its own analysis of data from the Mayo Clinic’s program of hospitalized patients who received plasma. Although the size of the benefit varied, he said in a statement, “there appears to be roughly a 35 percent relative improvement in the survival rates of patients” who received the plasma with higher versus lower levels of antibodies.

He added: “Given the safety profile observed, the totality of evidence regarding potential efficacy more than adequately met the ‘may be effective’ standard for granting an Emergency Use Authorization.”

-

The Resolve study in the UK has a convalescent plasma arm. When it reports we’ll get good data.

In the mean time I have no problem with the CP emergency approval. Just wish they wouldn’t exaggerate the impact. That’s not helpful.

@jon-nyc said in About that "convalescent plasma.":

In the mean time I have no problem with the CP emergency approval. Just wish they wouldn’t exaggerate the impact. That’s not helpful.

Yeah, the "35 out of 100 people would survive" comment in particular was exactly that: unhelpful.

-

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2031304?query=TOC

CONCLUSIONS

No significant differences were observed in clinical status or overall mortality between patients treated with convalescent plasma and those who received placebo. -

Convalescent Plasma Strikes Out As COVID-19 Treatment

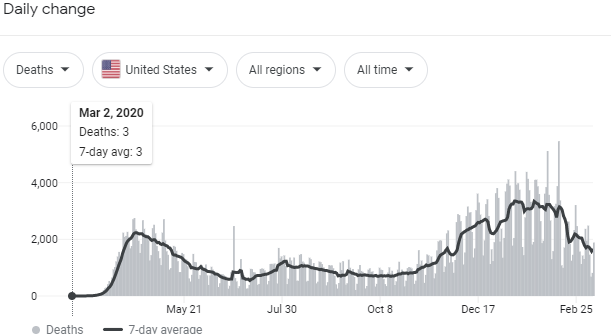

More than half a million Americans have received an experimental treatment for COVID-19 called convalescent plasma. But a year into the pandemic, it's not clear who, if anyone, benefits from it.

That uncertainty highlights the challenges scientists have faced in their attempts to evaluate COVID-19 drugs.

On paper, treatment with convalescent plasma makes good sense. The idea is to take blood plasma from people who have recovered from COVID-19 and infuse it into patients with active infections. The antibodies in the donated plasma, in theory, would help fight the virus.

Based on that idea, last March Dr. Nicole Bouvier at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York decided to give it a try.

She recalls thinking, "we have this new disease that didn't have any known therapies, and convalescent plasma has been used in new epidemic and pandemic diseases," as recently as in an Ebola outbreak in West Africa a few years ago.

She says she was the first doctor to get special permission from the Food and Drug Administration to use it as an experimental treatment.

It was a huge commitment to line up people willing to donate plasma as well as to treat patients themselves, "so it was a big production," she says. "We ultimately screened over 70,000 people" and identified around 20,000 who had high antibody levels in their blood plasma.

Mount Sinai treated more than 1,400 patients, including throughout the height of New York City's nightmarish COVID-19 outbreak last spring. But all the while Bouvier had no idea whether the plasma really worked.

Finally, a couple of weeks ago, she had seen enough data from carefully controlled studies — and decided to stop offering the treatment.

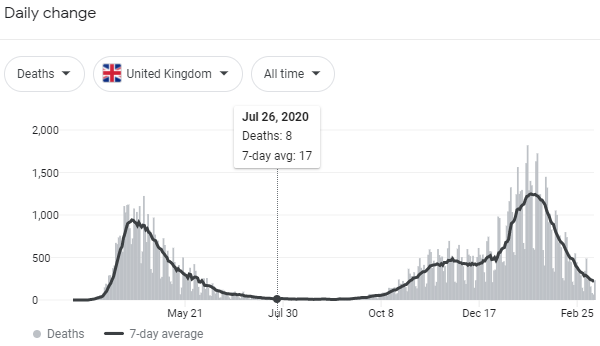

"The straw that broke the camel's back was two very large cohort trials," she says. The RECOVERY Trial in the United Kingdom had studied more than 10,000 volunteers and found no benefit. Another one called CONCOR-1, run by Canadians, had studied nearly 1,000 patients. It, too, stopped recruiting new patients because doing so would have been futile.

But those studies focused on people sick enough to be in the hospital. Dr. Arturo Casadevall at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health is one of the prime advocates for convalescent plasma. He says he thinks the treatment needs to be done sooner, in the outpatient setting.

"From the very beginning here at Hopkins we set out to do outpatient trials," he says. "The trials were set up in March [of 2020], however it took many months to get the money to do it." With taxpayer money nowhere to be found, the study ultimately went forward with funding from the billionaire Michael Bloomberg, Casadevall says.

A year later, the study at Hopkins still doesn't have results. And it's not just a question of funding. The entire U.S. medical research system isn't set up to do what's needed to identify new treatments during a pandemic.

image url)

image url) image url)

image url)