CFR

-

-

Our World In Data also makes the point that CFR is not necessarily the best measure of how things are progressing.

https://ourworldindata.org/covid-mortality-risk

What we want to know isn’t the case fatality rate: it’s the infection fatality rate

Before we look at what the CFR does tell us about the mortality risk, it is helpful to see what it doesn’t.

Remember the question we asked at the beginning: if someone is infected with COVID-19, how likely is it that they will die? The answer to that question is captured by the infection fatality rate, or IFR.

The IFR is the number of deaths from a disease divided by the total number of cases. If 10 people die of the disease, and 500 actually have it, then the IFR is [10 / 500], or 2%.3,4,5,6,7

To work out the IFR, we need two numbers: the total number of cases and the total number of deaths.

However, as we explain here, the total number of cases of COVID-19 is not known. That’s partly because not everyone with COVID-19 is tested.8,9

We may be able to estimate the total number of cases and use it to calculate the IFR – and researchers do this. But the total number of cases is not known, so the IFR cannot be accurately calculated. And, despite what some media reports imply, the CFR is not the same as – or, probably, even similar to – the IFR. Next, we’ll discuss why.

Interpreting the case fatality rate

In order to understand what the case fatality rate can and cannot tell us about a disease outbreak such as COVID-19, it’s important to understand why it is difficult to measure and interpret the numbers.

The case fatality rate isn’t constant: it changes with the context

Sometimes journalists talk about the CFR as if it’s a single, steady number, an unchanging fact about the disease. This is a particular bad example from the New York Times in the early days of the COVID-19 outbreak.

But it’s not a biological constant; instead, it reflects the severity of the disease in a particular context, at a particular time, in a particular population.

The probability that someone dies from a disease doesn’t just depend on the disease itself, but also on the treatment they receive, and on the patient’s own ability to recover from it.

This means that the CFR can decrease or increase over time, as responses change; and that it can vary by location and by the characteristics of the infected population, such as age, or sex. For instance, older populations would expect to see a higher CFR from COVID-19 than younger ones.

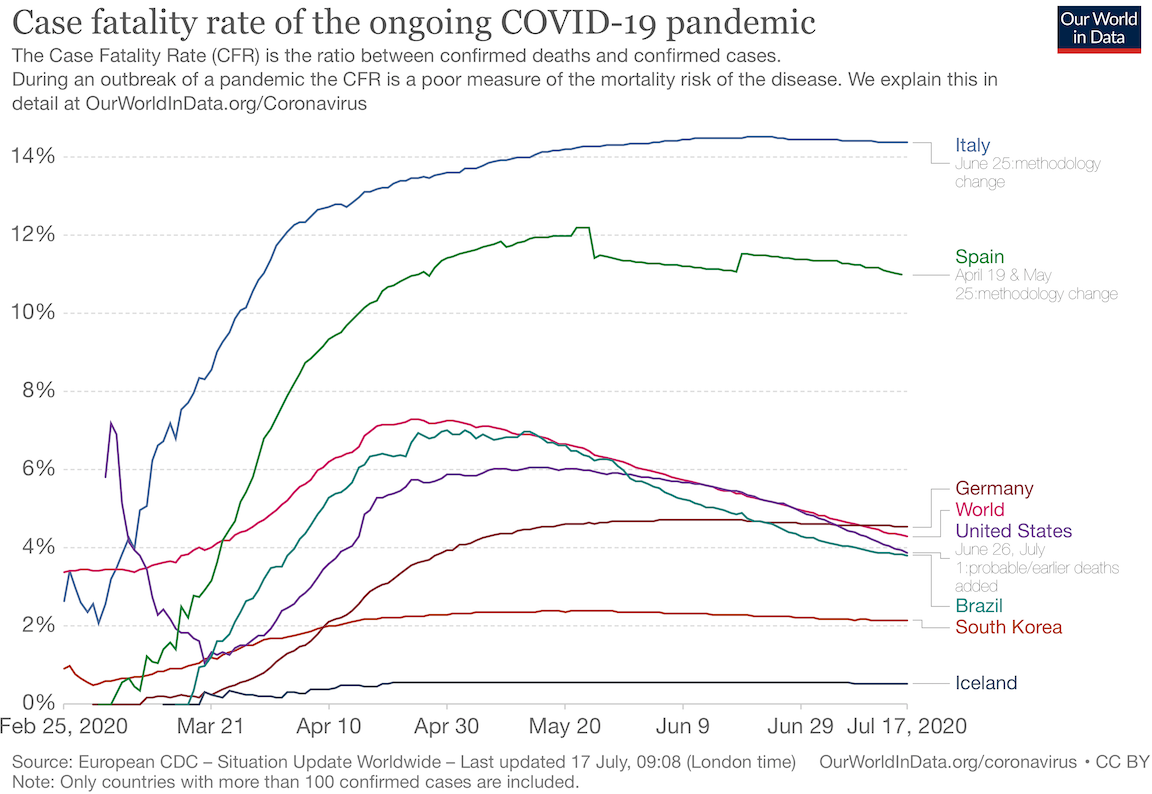

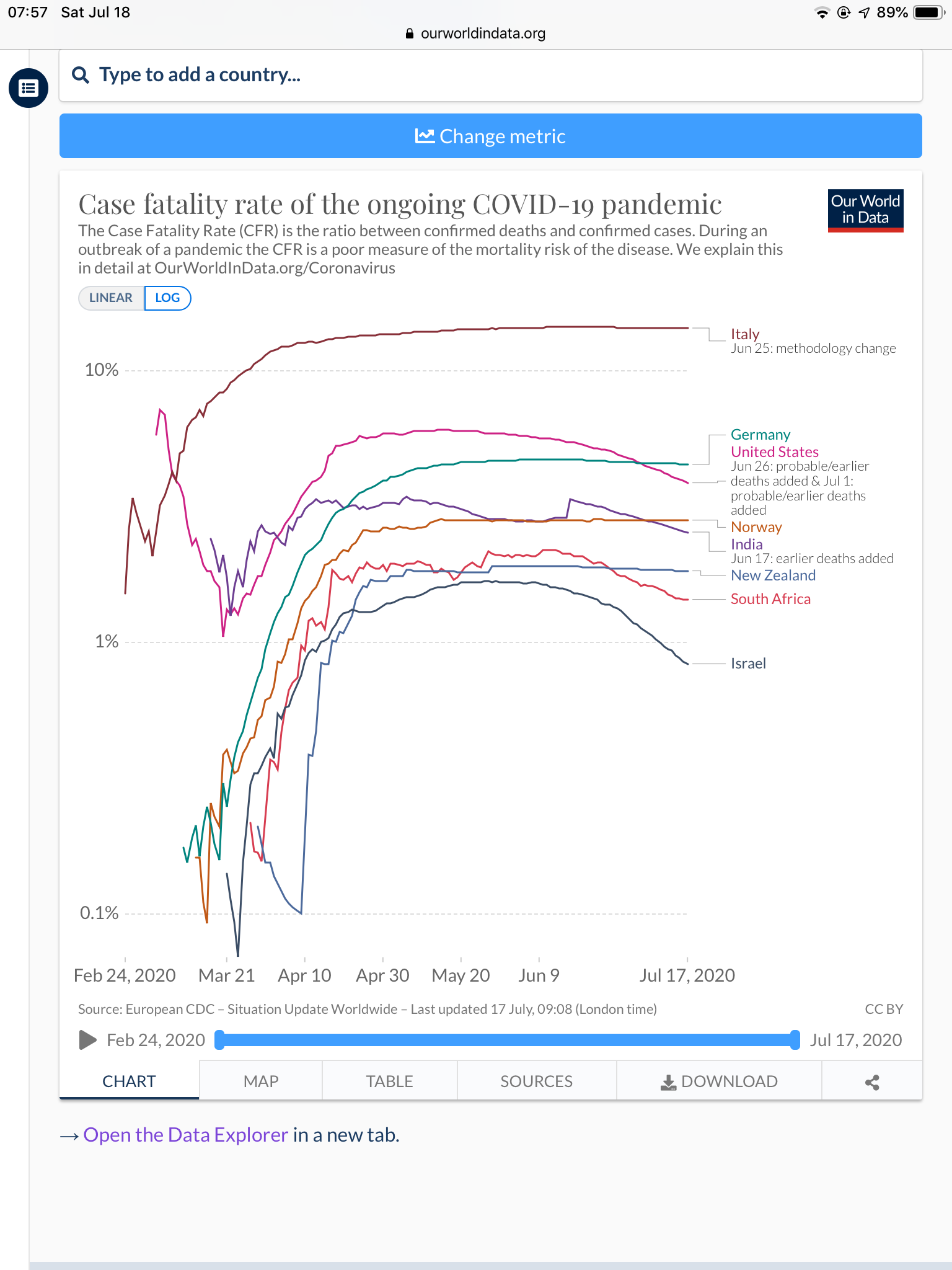

The CFR of COVID-19 differs by location, and has changed during the early period of the outbreak

The case fatality rate of COVID-19 is not constant. You can see that in the chart below, first published in the Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), in February 2020.10

It shows the CFR values for COVID-19 in several locations in China during the early stages of the outbreak, from the beginning of January to 20th February 2020.

You can see that in the earliest stages of the outbreak the CFR was much higher: 17.3% across China as a whole (in yellow) and greater than 20% in the centre of the outbreak, in Wuhan (in blue).

But in the weeks that followed, the CFR declined, reaching as low as 0.7% for patients who first showed symptoms after February 1st. The WHO says that that is because “the standard of care has evolved over the course of the outbreak”.

You can also see that the CFR was different in different places. By 1st February, the CFR in Wuhan was still 5.8% while it was 0.7% across the rest of China.

This shows that what we said about the CFR generally – that it changes from time to time and place to place – is true for the CFR of COVID-19 specifically. When we talk about the CFR of a disease, we need to talk about it in a specific time and place – the CFR in Wuhan on 23rd February, or in Italy on 4th March – rather than as a single unchanging value.

-

Apropos the Israel thread and our mortality rate