Is Britain's NHS broken?

-

From the New England Journal of Medicine (behind a paywall, so here's the entire article):

At Breaking Point or Already Broken? The National Health Service in the United Kingdom

David J. Hunter, M.B., B.S., F.Med.Sci.

“Crisis,” “collapse,” “catastrophe” — these are common descriptors from recent headlines about the National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom. In 2022, the NHS was supposed to begin its recovery from being perceived as a Covid-and-emergencies-only service during parts of 2020 and 2021. Throughout the year, however, doctors warned of a coming crisis in the winter of 2022 to 2023. The crisis duly arrived.

For much of December 2022 and January 2023, media reports featured ambulances lined up outside hospitals, unable to hand over their patients; patients lying at home with fractured hips, unattended by ambulances; emergency department waiting times exceeding 12 hours; and hospital corridors crowded with patients unable to be admitted. The Royal College of Emergency Medicine estimated in December that 300 to 500 people were dying each week because of these delays. Ambulance workers and nurses held their first strikes in 30 years over pay and conditions. In mid-March, mid-April, and mid-June, junior doctors held 3- or 4-day strikes — and senior doctors have scheduled similar action. Hundreds of thousands of operations and appointments have been canceled.

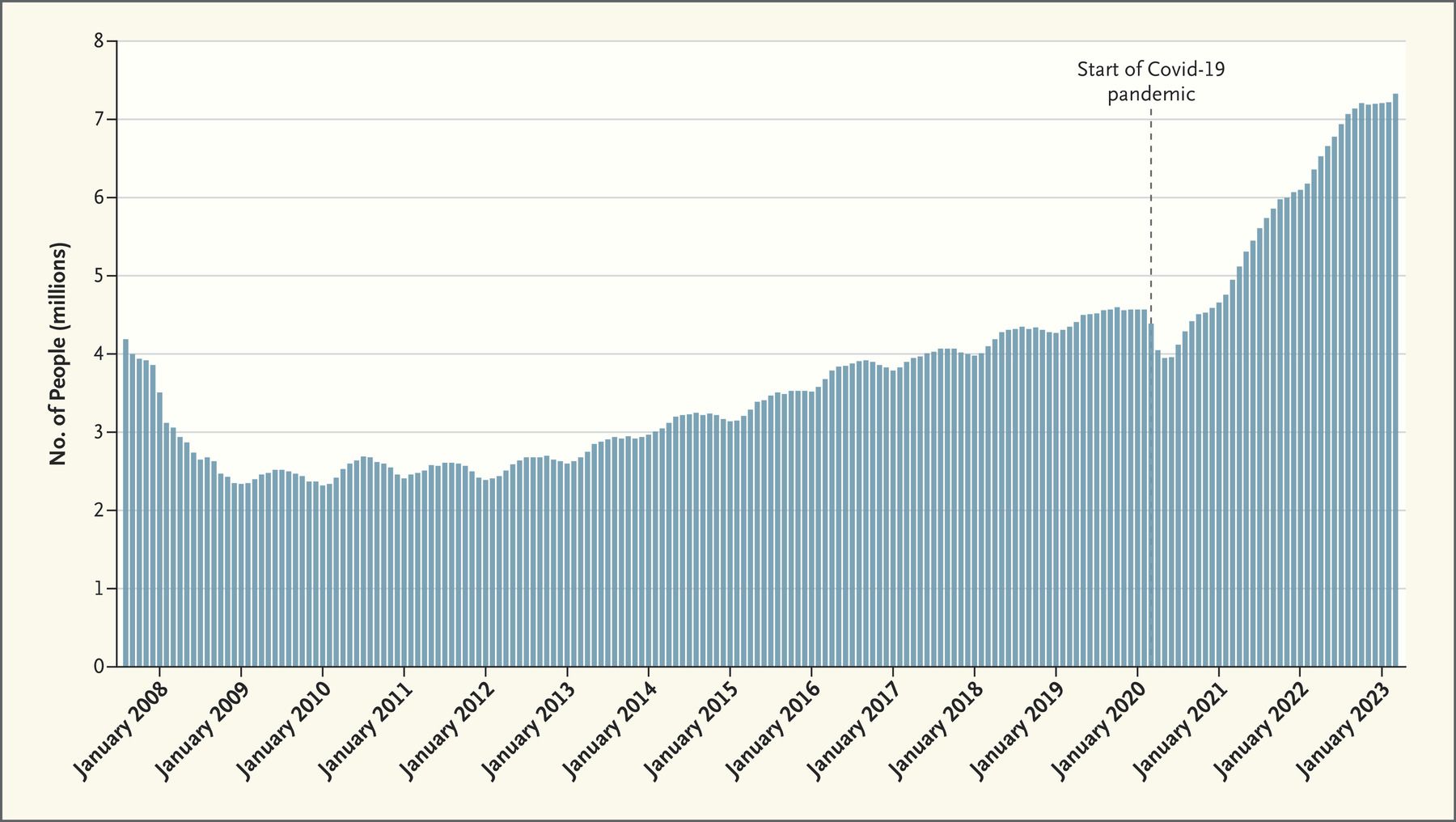

Number of People on National Health Service Waiting Lists for Consultant-Led Elective Care, August 2007 to March 2023.

In the background of this acute crisis, waiting lists for specialist consultation have been growing and now exceed 7 million patients (in a country of 66 million people), up from 4.4 million before the pandemic (see graph).1 There is substantial consensus about the causes of these crises, though different experts weight the contributory factors differently.

The primary contributor is long-term underinvestment in health services. The United Kingdom adhered to health system orthodoxy in reducing expenditures by running a “just-in-time” system with high hospital-bed occupancy. The number of hospital overnight beds per 1000 population declined by about 10% between 2010–2011 and 2019–2020, while the number of day-only beds increased by about 13%. In terms of beds per 1000 population, the country ranks second-lowest among 24 European countries, with 2.4 beds as compared with an average of 5.0 (and 7.8 in Germany).2 The minimal resilience built into the system made the large impact of a surge in pandemic-related hospitalizations unavoidable.

According to the World Bank, U.K. health system spending rose from 7.0% to 9.8% of the gross domestic product between 2000 and 2009, then plateaued at 10.2% in 2019, during the current governing party’s “austerity policy.” The country’s per-capita spending on health is about 18% lower than the median among 14 European countries. Although the government increased health spending during the pandemic, and again in recent months in an attempt to reduce waiting lists, we are relearning the lesson that the effects of a decade of underinvestment cannot be rapidly reversed. Some of the additional short-term funding is siphoned off to pay for more expensive locum agency personnel and other stopgap solutions.

The NHS’s dependence on nursing homes and aged care facilities is another key contributor to the crisis. The dearth of hospital beds derives partly from “bed blocking,” caused by unavailability of beds in aged care facilities for patients who are fit for discharge. In January, such patients occupied approximately one in seven acute care beds, which caused long admission delays. Multiple reports have warned that the elder care system is inadequate owing to the low fees paid for government-funded residents, and it faces a workforce crisis. Managers report dreading the opening of a new local supermarket because its hourly wages will be higher than what they can pay staff. And an older population requires more NHS treatment and more resources from the elder care system.

The crisis also reflects demand created by a sicker population, seasonal influenza, and the Covid-19 pandemic. The prevalence of undiagnosed and undertreated hypertension and hypercholesterolemia is high in the United Kingdom, which also has the highest prevalence of obesity among large European countries — burdens that increase demand on the NHS. An early and severe influenza season was a tipping point this winter. Covid-19 persists, and on some days in early January, more than 12,000 inpatients had confirmed Covid-19 infections — not that far short of the 20,000 patients admitted at the peak of the first wave in mid-April 2020, though daily Covid-19 mortality was 90% lower.

Meanwhile, the workforce is both inadequate and exhausted. Like the United States, the United Kingdom trains only a fraction of the health care professionals it needs, assuming that it can import the rest. Astonishingly, since 2014, the number of cardiothoracic surgeons in the United Kingdom who initially trained elsewhere in Europe has exceeded the number of those trained domestically.3 Brexit partially reversed this trend, reducing the inflow of European health professionals, especially nurses, beginning well before the pandemic hit.3 Over the past 10 years, U.K. nurses’ wages have decreased by about 10% in real terms, contributing to early retirements and resignations. Junior doctors’ real salaries have decreased by more than 25%. In primary care in England, the number of qualified general practitioners (GPs) per 1000 population fell from 0.52 in 2015 to 0.44 in 2023, while the average number of patients per GP increased by 17%.4 In addition, more than two thirds of GP trainees anticipate that they won’t be working full time a year after they finish their training, citing unmanageable workloads.5 The U.K. government’s short-term response is to scavenge health workers from lower-income countries that can ill afford to lose the staff they have trained at considerable cost. A workforce plan released in early July will take years to materialize new staff and does not address the immediate causes of the strikes.

Employment idiosyncrasies have exacerbated these trends. The U.K. tax system penalizes workers once they accumulate £1 million in their “pension pot.” Since many doctors hit this amount in their 50s, and since NHS employees must contribute a fixed percentage of income to their pension savings, the only way they could avoid punitive tax penalties is to earn less — by withdrawing their labor from the system well before they reach a standard retirement age. Changes to pension rules announced in March 2023 may slow this exodus but will take years to filter through to the clinic.

Finally, burnout and low morale due to pandemic-related exhaustion combined with the decline in real wages has led to decreases in the proportion of staff who feel adequately recognized and rewarded and would recommend the NHS as a place to work. Even though strike action is the last resort for most health professionals, the government has characterized NHS workers’ wage demands as a recipe for inflation rather than acknowledging the legitimate problem of the decline in real wages, further undermining morale.

It is hardly surprising that public confidence in the NHS has fallen sharply. The unspoken agreement between the NHS and U.K. residents was that despite some rationing of care, regional differences in service availability, and the often aging and less-than-sparkling premises, in the event of a medical emergency, an ambulance would arrive promptly and high-quality care would be available at a hospital without anyone requiring an insurance card. That agreement has been broken, and satisfaction with the service is at record lows. Nevertheless, a majority of people polled support the striking medical workers, recognizing that their salaries have not matched the cost of living and that working conditions are often intolerable.

To many Britons, the entire system feels broken, but there is little consensus on how to repair it. Both major political parties agree that increased government funding is not the only solution and call for NHS “reforms,” but they disagree on the shape of those reforms. The NHS has undergone many rounds of structural reforms without reaching a sustainable equilibrium. The Conservative government is accused of deliberately underfunding the NHS in order to force patients into private health care and usher in a two-tier system. If that’s the intention, it ignores the fact that though private capital might support building of more facilities, most of the clinical staff would be trained over many years in the NHS, which would make staffing a zero-sum game. There is broad agreement that better integration of primary care with hospital-based and social care is urgently needed, along with better-integrated medical record systems and a focus on disease prevention. However, the entire health system feels as though it’s waiting for a change of government, without much confidence that a new government would provide the additional funding necessary for integration, hospital renovations, and workforce expansion.

The state of the NHS makes for much misery among patients and frustration among already exhausted health professionals. And the rest of the world should care as well: 75 years ago, the United Kingdom became the first large country to make health services “free at the point of care” and paid for by collective taxation, and the NHS has become the model for many other systems that seek to remove the profit motive from health care provision in the name of equity and cost control. As goes the NHS, so goes this paradigm.

@George-K said in Is Britain's NHS broken?:

The United Kingdom adhered to health system orthodoxy in reducing expenditures by running a “just-in-time” system with high hospital-bed occupancy. The number of hospital overnight beds per 1000 population declined by about 10% between 2010–2011 and 2019–2020, while the number of day-only beds increased by about 13%. In terms of beds per 1000 population, the country ranks second-lowest among 24 European countries, with 2.4 beds as compared with an average of 5.0 (and 7.8 in Germany).

This is interesting, because I have hear about hospital closing a lot in the US. It appears that the hospital bed/1000 people is about the same as UK.

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.BEDS.ZS?locations=US

7.9 beds/1000 people in 1970 to about 2.4 beds/1000 people in today.

Is part of the decrease due to insurance companies not wanting people to stay longer in the hospitals?

-

It’s worth noting that for my entire life people have been saying the NHS is in its final throes. My mother got pretty decent healthcare when she broke her hip in 2020. It’s not the same as the US, but neither is the how much people need to pay.

It does feel that it’s currently a bigger crisis than normal, however

-

@George-K said in Is Britain's NHS broken?:

The United Kingdom adhered to health system orthodoxy in reducing expenditures by running a “just-in-time” system with high hospital-bed occupancy. The number of hospital overnight beds per 1000 population declined by about 10% between 2010–2011 and 2019–2020, while the number of day-only beds increased by about 13%. In terms of beds per 1000 population, the country ranks second-lowest among 24 European countries, with 2.4 beds as compared with an average of 5.0 (and 7.8 in Germany).

This is interesting, because I have hear about hospital closing a lot in the US. It appears that the hospital bed/1000 people is about the same as UK.

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.BEDS.ZS?locations=US

7.9 beds/1000 people in 1970 to about 2.4 beds/1000 people in today.

Is part of the decrease due to insurance companies not wanting people to stay longer in the hospitals?

@taiwan_girl said in Is Britain's NHS broken?:

@George-K said in Is Britain's NHS broken?:

The United Kingdom adhered to health system orthodoxy in reducing expenditures by running a “just-in-time” system with high hospital-bed occupancy. The number of hospital overnight beds per 1000 population declined by about 10% between 2010–2011 and 2019–2020, while the number of day-only beds increased by about 13%. In terms of beds per 1000 population, the country ranks second-lowest among 24 European countries, with 2.4 beds as compared with an average of 5.0 (and 7.8 in Germany).

This is interesting, because I have hear about hospital closing a lot in the US. It appears that the hospital bed/1000 people is about the same as UK.

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.BEDS.ZS?locations=US

7.9 beds/1000 people in 1970 to about 2.4 beds/1000 people in today.

Is part of the decrease due to insurance companies not wanting people to stay longer in the hospitals?

No, it's because longer stays are not necessary in most cases. For instance, a hip transplant is now most often outpatient surgery. This is an advance.

-

@George-K said in Is Britain's NHS broken?:

The United Kingdom adhered to health system orthodoxy in reducing expenditures by running a “just-in-time” system with high hospital-bed occupancy. The number of hospital overnight beds per 1000 population declined by about 10% between 2010–2011 and 2019–2020, while the number of day-only beds increased by about 13%. In terms of beds per 1000 population, the country ranks second-lowest among 24 European countries, with 2.4 beds as compared with an average of 5.0 (and 7.8 in Germany).

This is interesting, because I have hear about hospital closing a lot in the US. It appears that the hospital bed/1000 people is about the same as UK.

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.BEDS.ZS?locations=US

7.9 beds/1000 people in 1970 to about 2.4 beds/1000 people in today.

Is part of the decrease due to insurance companies not wanting people to stay longer in the hospitals?

@taiwan_girl said in Is Britain's NHS broken?:

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.BEDS.ZS?locations=US

Interesting. It seems only China, South Korea, and Turkey show upward trends with that hospital beds/100,000 population metric.

Lots of countries struggle with having rapidly aging demographics, yet with the exception of the above, most of their beds/population measures show downtrends.

Amazingly, Japan and South Korea tower over all others with 13 and 12.4 beds per 100,000 population.

-

@George-K said in Is Britain's NHS broken?:

Another round of applause for healthcare workers probably isn’t going to cut it