Hay George

-

Sure...

Bond Market Sends Warning to Trump and Republicans on Tax Plans

As yields rise, higher borrowing costs potentially push the GOP to increase its focus on spending cutsJan. 15, 2025 at 6:24 pm

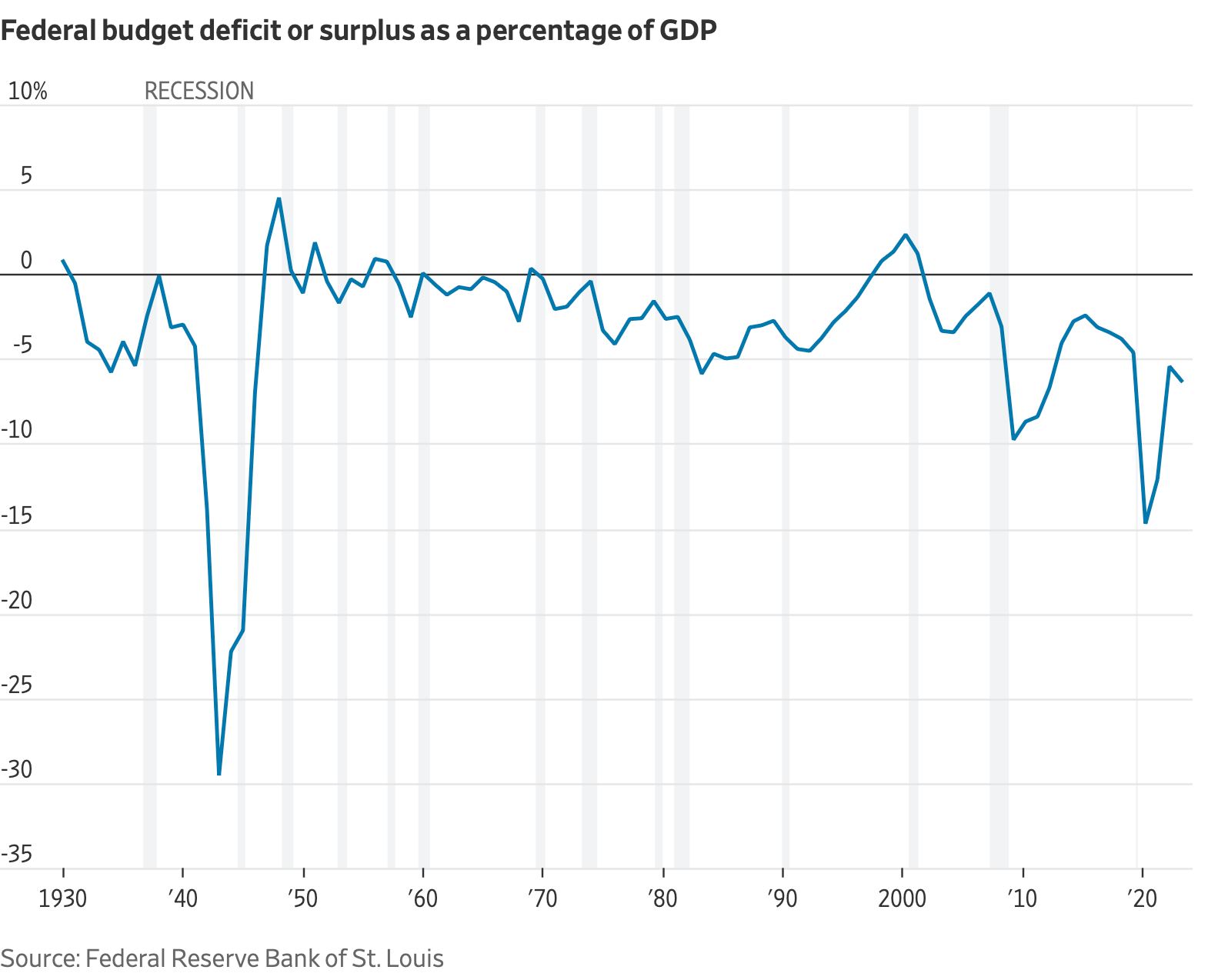

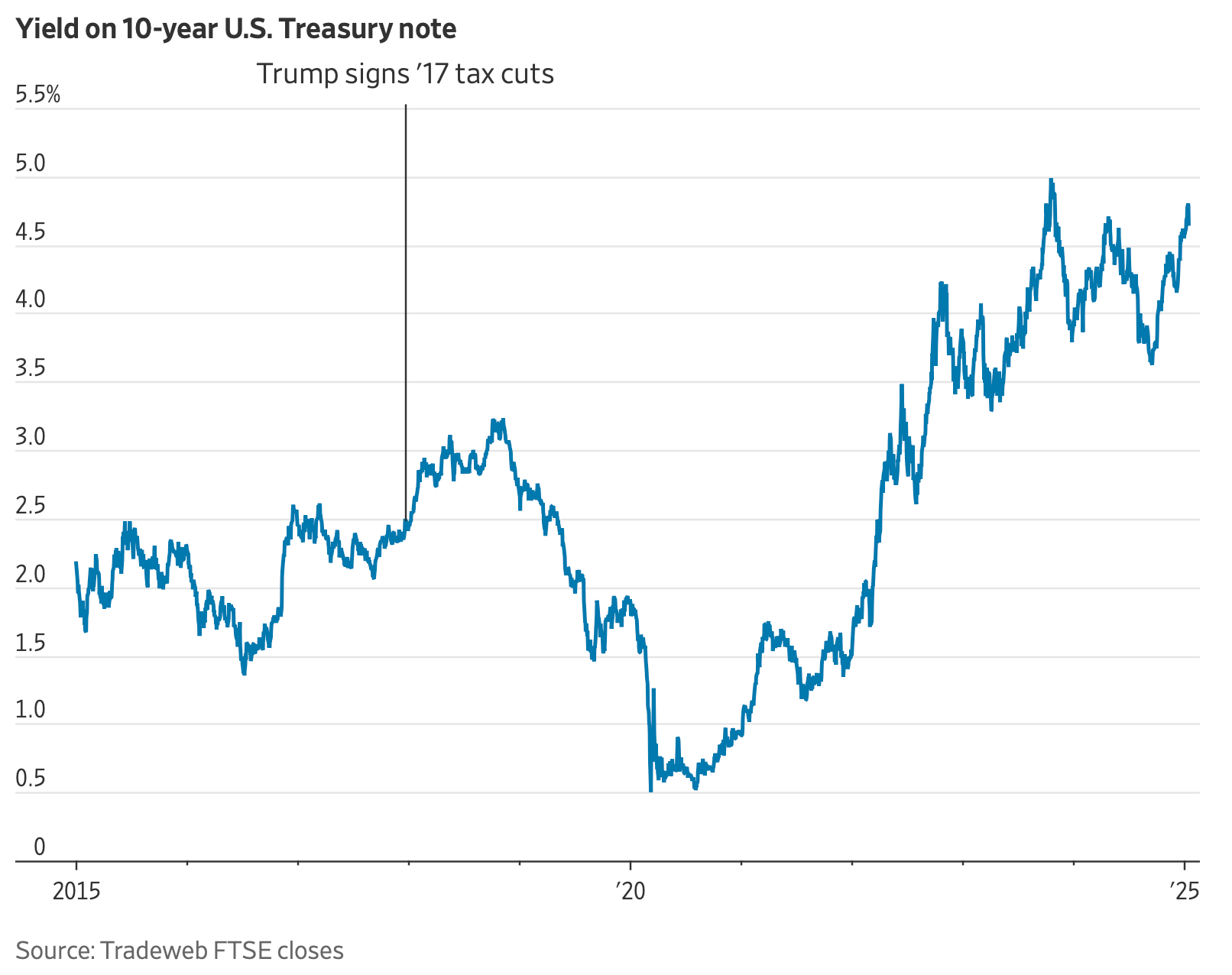

As Republicans retake full control of the government and weigh taking on more debt, they face a much trickier fiscal and financial environment than they did during Donald Trump’s first term. Interest rates are much higher and budget deficits much larger. U.S. government bonds have endured a particularly steep selloff over the past few months, making the deficit an even bigger burden.

Tumbling bond prices have driven up the yield on the benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury note to 4.8% in recent days, though it slipped Wednesday to 4.65% after fresh inflation data. That is up around 1 percentage point from September and a far cry from the 2% yields that prevailed in 2017, when Republicans enacted a $1.5 trillion deficit-financed tax cut.

Bond investors’ increasing premium for U.S. government debt poses a tough challenge for the new GOP Congress and for Scott Bessent, Trump’s pick for Treasury secretary. Bessent, who is sitting for his confirmation hearing on Thursday, has talked about boosting economic growth and trimming deficits roughly in half, to 3% of gross domestic product. But Republicans are also proposing several deficit-increasing policies: extending expiring tax cuts, fulfilling Trump’s additional tax-cut promises, increasing border-security spending and boosting national defense.

“They should have been concerned in ’17 about deficits,” said Michael Strain, an economist at the conservative-leaning American Enterprise Institute. “They should be even more concerned in ’25 about deficits.”

At the new, higher interest rates, every decision to borrow more money costs even more money. Every 0.1-percentage-point increase in Treasury borrowing costs adds more than $300 billion in interest expenses over a decade. The more the U.S. borrows, the less capital is available for the private sector. And the higher bond yields climb, generally, the more U.S. consumers pay for mortgages, auto loans and credit cards.

House Republicans discussed the interplay between the bond market and their fiscal plans during a closed-door session Wednesday on their still-developing tax plans, according to lawmakers. The bond-market pressure could restrain their tax cuts or lead them toward spending cuts.

“If we can convince the bond market that we’re actually getting serious about fiscal responsibility, that will send a virtuous signal to the bond market that will start lowering that 10-year,” said Rep. Andy Barr (R., Ky.). “This is not austerity. This is not painful cuts. This is about lowering your mortgage payment.”

Broadly, Republicans express alarm about the U.S. fiscal path while rejecting tax increases and splitting over spending cuts. So by and large, GOP lawmakers see economic growth as the path to smaller deficits. They see tax cuts—which widen deficits, particularly in the short term—as crucial to growth. Extending the expiring tax cuts could increase deficits by about $5 trillion over a decade, and Republicans said it is essential to maintain those Trump policies and even do more.

“It looks like interest rates may be going back up a bit,” said Senate Finance Committee Chairman Mike Crapo (R., Idaho). “I don’t know that it changes anything because we’re focused on economic growth, and whether the bond market is stumbling or whether it’s not, the same principles apply.”

Typically, tax cuts don’t pay for themselves, and economists don’t expect extending most of the expiring tax cuts for households to yield a major long-term growth boost. Some pieces, including business investment incentives, could have a bigger growth effect, and smaller budget deficits could also improve the economy. After the 2017 tax cuts, investment increased and revenue exceeded forecasts, but that doesn’t mean the tax cuts generated enough growth to pay for themselves; the Congressional Budget Office said most of the higher nominal revenue was due to inflation.

Skepticism about deficit reduction

For the past few decades, bond markets haven’t restrained U.S. fiscal policy. Fear of so-called bond-market vigilantes helped drive deficit-reduction deals in the 1980s and early 1990s. But particularly since the 2008-09 financial crisis, U.S. borrowing costs stayed historically low as deficits and debt climbed. Congresses and presidents in both parties cut taxes and increased spending, widening the structural gap between revenue and outlays.

The bond market’s latest slump started before the election and accelerated afterward, leading a sharp rise in yields around the developed world. A run of strong economic data contributed to the selloff, causing investors to scale back expectations for how much the Federal Reserve would cut interest rates in 2025—though investors still aren’t betting that the central bank will start raising rates.

Politics have also been a factor. Many bond investors worry that Trump and congressional Republicans will pursue policies—tax cuts, tariffs and deportations—that could boost inflation and make rate cuts more unlikely. They also fear that Republicans will expand budget deficits, putting upward pressure on yields by forcing the Treasury Department to issue even more bonds into the market.

“In a very basic sense, it doesn’t matter why the 10-year is going up. What matters is that it is going up,” Strain said. “Borrowing costs are higher, and that kind of means we should be doing less borrowing.”

Investors and forecasters have been assuming that Republicans will extend expiring tax cuts with few spending cuts attached, said Alec Phillips, chief U.S. political economist at Goldman Sachs. The remaining uncertainties revolve around additional tax cuts and whether spending cuts accompany those.

“I don’t think there’s a widespread view that there’s going to be substantial deficit reduction,” he said.

Watching the markets

Lawmakers usually pay far less attention to bond markets than to stocks, which they tend to view as a barometer of economic health.

But the U.S. could be re-entering a period in which borrowing costs and structural budget deficits shape long-term policy decisions. As the world’s haven, the U.S. has more borrowing room than other major countries. What’s hard to determine is how high U.S. debt can go without significantly restraining economic growth.

“We don’t know where that magical number is, but we know we’re close,” said Sen. Thom Tillis (R., N.C.). “So that’s, to me, what the markets are beginning to respond to.”

Some Senate Democrats recently asked Republicans to consider a bipartisan tax-cut extension; Democrats favor letting tax cuts for higher-income households expire.

“A fully deficit-financed, partisan effort could risk raising costs for families, driving up interest rates for Americans looking to purchase a home, and increasing borrowing costs for American businesses and consumers,” they wrote, led by Sens. Catherine Cortez Masto (D., Nev.) and Mark Warner (D., Va.).

What’s the plan?

So far, Republicans are trying to find votes in their own ranks. They haven’t decided on a fiscal outline for the tax bill, and settling on that could be contentious.

Crapo argues that Congress should assume that the tax cuts’ extension doesn’t have a cost because it is just continuing current policies. But in the House, some conservatives are seeking significant spending cuts alongside tax-cut extensions. House Budget Committee Chairman Jodey Arrington (R., Texas) has circulated more than $5 trillion on a menu of options, largely focused on Medicaid and other health programs.

With the House divided 219-215—and that majority temporarily shrinking to 217-215 once lawmakers join the Trump administration—just a few House deficit hawks concerned about bond markets could pull the party toward spending cuts.

Rep. Tom McClintock (R., Calif.) said Congress should give priority to tax cuts that have the best chance of boosting productivity growth. To him, that means emphasizing marginal rate cuts and delaying changes to the state and local tax deduction and Trump’s plans to eliminate taxes on tips and Social Security benefits.

McClintock said that tax cuts must be accompanied by spending cuts and that he hopes the bill would result in lower deficit spending.

“I’m very concerned that we’re entering a debt spiral, where bond markets are going to be requiring additional interest to buy federal debt,” McClintock said. “That becomes a debt spiral. That never ends well.”