Puzzle time - flipping the pentagon

-

Got it.

:::

Let l-0 to l-4 be the label values.The partial sums are:

P-0 = 0

P-i = P-(i-1) + l-(i modulo 5)Obviously, for every i, P-(i+5) = P-i + s, where s is the sum of l-0 to l-4. So the sequence of P-i is

roughly sorted, but there are sorting errors in between.More precisely, let e-i be the number of sorting errors at i, defined as follows:

e-i = the number of j > i with P-j < P-i.

e-i is finite because the sum of labels is positive.

Now consider the sum of errors E = e-0 + ... + e-4.

Every flip decreases E by one, hence we are done after E steps.

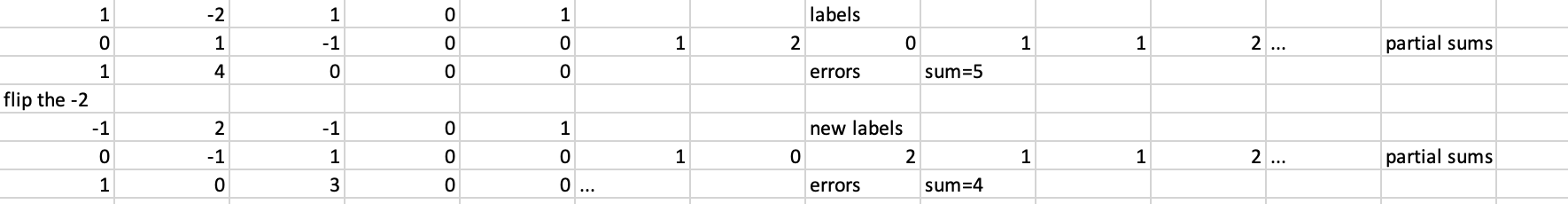

Example with the "critical case" of a flip turning two positive numbers negative.

The error sum in the beginning is 5 and indeed we are done after 5 flips. We see how the error values 4 and 0 are swapped by the flip, but after the flip the 4 is decreased by one to 3. All other errors stay the same.

So my method also gives you the number of required flips. And it generalizes easily to more than 5 labels.

:::

-

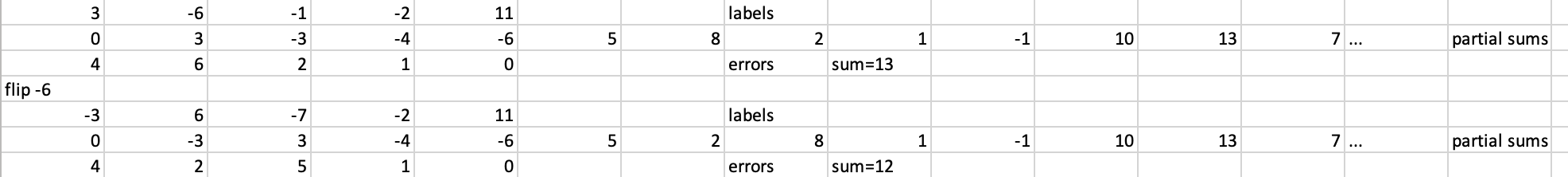

No, it works fine on your example.

The required number of flips decreases from 13 to 12 after flipping the -6.

Try it out and you'll see that you'll indeed need 13 flips for the example, which is exactly the sum of sorting errors predicted by my method.

In the general case, if you flip l-i, then the new e-i is the old e-(i+1) and the new e-(i+1) is the old e-i minus one: all other e-j stay the same. Hence the sum of e-0 to e-4 decreases by 1 with each flip.

-

Never flipped the Pentagon, but I’ve flipped off Capitol Hill.

-

I've implemented my method of calculating the number of required flips as a program.

You can execute the program and try it with different examples.

What you see is what it does to Jon's example.

Just press "Run".

-

I've also used the code to create examples that maximize the number of required flips.

For instance, within the range of numbers between -10 and +10, the examples

that are "maximal" with regard to required flips need 96 flips. Here's one such example:10, 10, 1, -10, -10

-

That's great Klaus. I have three solutions, all different from yours:

The problem showed up on the 1986 International Mathematics Olympiad (held in Poland) and ten of the eleven competitors who got it right found that if you take the sum of the squares of the differences between non-adjacent numbers, it works!

Suppose the numbers are, reading around the pentagon, A, B, C, D, and E. Then the sum in question is S = (A-C)2 + (B-D)2 + (C-E)2 + (D-A)2 + (E-B)2. Suppose B is negative and we flip it, replacing B by -B, A by A+B, and C by C+B. Then the new S is equal to the old S plus 2B(A+B+C+D+E), and since B is negative and A+B+C+D+E is positive, S goes down. And since S is an integer, it goes down by at least 1.

But S is non-negative (being a sum of squares) so it can't go below zero. That means we must reach a point where there's no negative entry left to flip, and we are done.

What about that eleventh correct competitor? He was an American, Joseph Keane, and his solution was even better — and won him a special prize — because it worked for all polygons, not just the pentagon. Joseph's measure of progress was the sum, over all sets of consecutive vertices, of the absolute value of the sum of the numbers in the set.

An even more amazing solution (in my opinion) was later found by Princeton computer scientist Bernard Chazelle. Construct a doubly-infinite sequence of numbers whose successive differences are the pentagon (or polygon) values, reading clockwise around the figure. In the example above, where the labels began as 1, 2, -2, -3, 3, the sequence might be:

. . . , -1, 0, 2, 0, -3, 0, 1, 3, 1, -2, 1, 2, 4, 2, -1, 2, 3, 5, . . .

Notice that the sequence climbs gradually (since the sum of the numbers around the polygon is positive) but not steadily (since some of the numbers around the polygon are negative).

Now the key observation: flipping a vertex has the effect of transposing pairs of entries of the above sequence that were in the wrong order — in other words, the flipping process turns into a sorting process for our infinite sequence!

For example, if we flip the -2 on our pentagon to get 1, 0, 2, -5, 3, the sequence changes to:

. . . , -1, 0, 0, 2, -3, 0, 1, 1, 3, -2, 1, 2, 2, 4, -1, 2, 3, 3, . . .

It turns out to be easy to measure the sorting progress and determine that, not only does it always terminate, but it terminates in the same number of steps and in the same final configuration, no matter what vertices you flip!

-

Yes, it seems to be the same solution indeed. In that solution, the partial sums of both clock-wise and anti-clockwise movement are used and I use only one direction (hence my list of partial sums is only singly-infinite, not doubly-infinite), but I think that's a superficial difference.

Nice! But I do have an unfair advantage in this case: It's somewhat similar to things I do for a living (such as: proving termination or confluence of certain state transition systems in theoretical computer science).