Speaking of dates in the past.

-

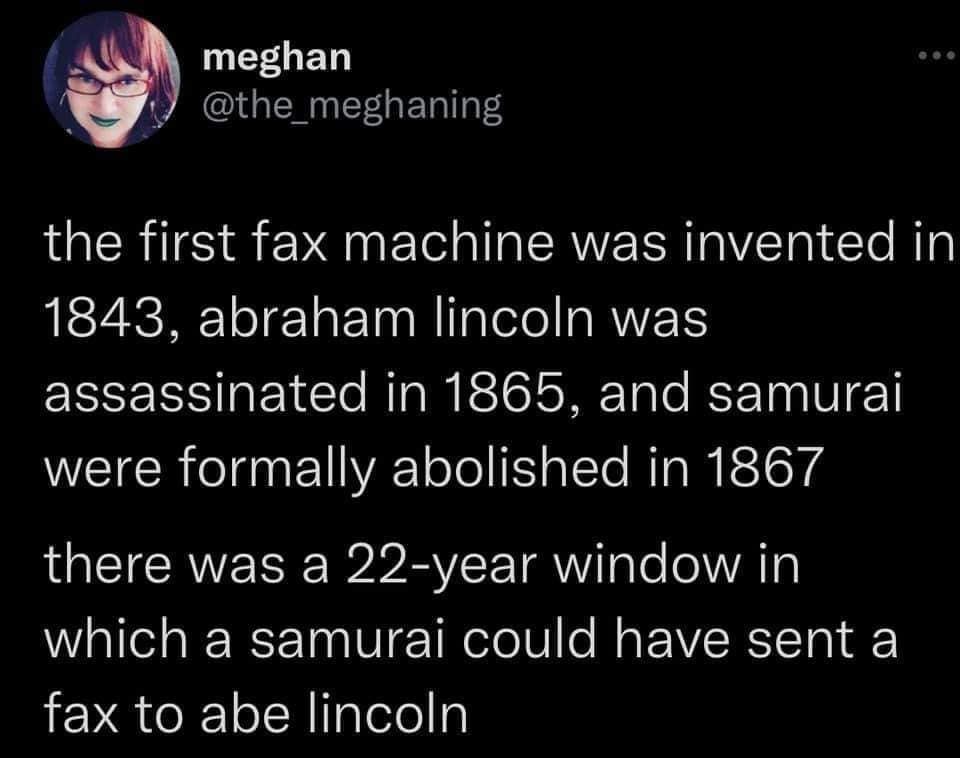

Yeah, think on THIS:

https://www.efax.com/blog/brief-history-of-the-fax-machinef there’s one invention that’s benefited from the passage of time, it’s the fax machine. Invented back in 1843 by Alexander Bain, the first fax machine was a far cry from the compact fax machines we know today.

The image quality was poor and transmissions were less than expedient. Considering the technology at the time, though, this was to be expected. Bain used “pendulums” and a “clock” to synchronize and capture images on a line by line basis – not exactly a speedy way of doing things. The images were then reproduced, giving way to the first fax.

It wasn’t until English physicist Frederick Bakewell improved on Bain’s original “fax machine” that faxing began to take shape – although not at breakneck speed. Bakewell’s fax machine used “rotating cylinders” and a “stylus” to create faxes. In spite of debuting at the 1851 World’s Fair in London to curious stares, it failed to be a runaway hit. Thankfully, Bakewell’s fax machine served as a blueprint from which other inventors could later draw inspiration.

By the late 1860s, Giovanni Caselli had come up with a fax machine known as the Pantelegraph. Unlike its predecessors, though, it was a hit – forming the basis of the modern-day fax machine. It would take another century before fax technology truly found its stride, though.

-

Yeah, think on THIS:

https://www.efax.com/blog/brief-history-of-the-fax-machinef there’s one invention that’s benefited from the passage of time, it’s the fax machine. Invented back in 1843 by Alexander Bain, the first fax machine was a far cry from the compact fax machines we know today.

The image quality was poor and transmissions were less than expedient. Considering the technology at the time, though, this was to be expected. Bain used “pendulums” and a “clock” to synchronize and capture images on a line by line basis – not exactly a speedy way of doing things. The images were then reproduced, giving way to the first fax.

It wasn’t until English physicist Frederick Bakewell improved on Bain’s original “fax machine” that faxing began to take shape – although not at breakneck speed. Bakewell’s fax machine used “rotating cylinders” and a “stylus” to create faxes. In spite of debuting at the 1851 World’s Fair in London to curious stares, it failed to be a runaway hit. Thankfully, Bakewell’s fax machine served as a blueprint from which other inventors could later draw inspiration.

By the late 1860s, Giovanni Caselli had come up with a fax machine known as the Pantelegraph. Unlike its predecessors, though, it was a hit – forming the basis of the modern-day fax machine. It would take another century before fax technology truly found its stride, though.

@george-k said in Speaking of dates in the past.:

Yeah, think on THIS:

https://www.efax.com/blog/brief-history-of-the-fax-machinef there’s one invention that’s benefited from the passage of time, it’s the fax machine. Invented back in 1843 by Alexander Bain, the first fax machine was a far cry from the compact fax machines we know today.

The image quality was poor and transmissions were less than expedient. Considering the technology at the time, though, this was to be expected. Bain used “pendulums” and a “clock” to synchronize and capture images on a line by line basis – not exactly a speedy way of doing things. The images were then reproduced, giving way to the first fax.

It wasn’t until English physicist Frederick Bakewell improved on Bain’s original “fax machine” that faxing began to take shape – although not at breakneck speed. Bakewell’s fax machine used “rotating cylinders” and a “stylus” to create faxes. In spite of debuting at the 1851 World’s Fair in London to curious stares, it failed to be a runaway hit. Thankfully, Bakewell’s fax machine served as a blueprint from which other inventors could later draw inspiration.

By the late 1860s, Giovanni Caselli had come up with a fax machine known as the Pantelegraph. Unlike its predecessors, though, it was a hit – forming the basis of the modern-day fax machine. It would take another century before fax technology truly found its stride, though.

I pwn3d the shit out of this some months back.

-

I worked for the government in the 1970s. We were required to have a fax machine. It cost over $3,000, took forever to produce a crappy image. In the 5 years I was there, we got one fax which was a single sheet, a two paragraph document that was of minimal importance.

It was as useful as the cone of science on Get Smart.

-

I worked for the government in the 1970s. We were required to have a fax machine. It cost over $3,000, took forever to produce a crappy image. In the 5 years I was there, we got one fax which was a single sheet, a two paragraph document that was of minimal importance.

It was as useful as the cone of science on Get Smart.

-

@kluurs said in Speaking of dates in the past.:

It was as useful as the cone of science on Get Smart.

What did you say?

@george-k said in Speaking of dates in the past.:

@kluurs said in Speaking of dates in the past.:

It was as useful as the cone of science on Get Smart.

What did you say?

Doh!! "Cone of Silence!"

They will put me in a home soon.

-

@george-k said in Speaking of dates in the past.:

@kluurs said in Speaking of dates in the past.:

It was as useful as the cone of science on Get Smart.

What did you say?

Doh!! "Cone of Silence!"

They will put me in a home soon.

-

@george-k said in Speaking of dates in the past.:

Yeah, think on THIS:

https://www.efax.com/blog/brief-history-of-the-fax-machinef there’s one invention that’s benefited from the passage of time, it’s the fax machine. Invented back in 1843 by Alexander Bain, the first fax machine was a far cry from the compact fax machines we know today.

The image quality was poor and transmissions were less than expedient. Considering the technology at the time, though, this was to be expected. Bain used “pendulums” and a “clock” to synchronize and capture images on a line by line basis – not exactly a speedy way of doing things. The images were then reproduced, giving way to the first fax.

It wasn’t until English physicist Frederick Bakewell improved on Bain’s original “fax machine” that faxing began to take shape – although not at breakneck speed. Bakewell’s fax machine used “rotating cylinders” and a “stylus” to create faxes. In spite of debuting at the 1851 World’s Fair in London to curious stares, it failed to be a runaway hit. Thankfully, Bakewell’s fax machine served as a blueprint from which other inventors could later draw inspiration.

By the late 1860s, Giovanni Caselli had come up with a fax machine known as the Pantelegraph. Unlike its predecessors, though, it was a hit – forming the basis of the modern-day fax machine. It would take another century before fax technology truly found its stride, though.

I pwn3d the shit out of this some months back.

I remember that.

-

I want to know how an 1843 fax machine worked.

I would have guessed that fax was invented way later, at least by 100 years.

How did they "read" the image? What was the encoding/decoding like? How did they "print" it?

@klaus said in Speaking of dates in the past.:

I want to know how an 1843 fax machine worked.

https://electronics.howstuffworks.com/gadgets/fax/history-of-fax.htm

The process Bain used relied on electrochemistry and mechanics, which he mastered during his days as an instrument and clock maker. Bain saw that telegraphs of the day were slowed by simple mechanics. He also noted that invention relied on electrical impulse, which he thought could be harnessed in a way that would create visual messages, speeding the process.

The chemical telegraph Bain invented, which would later be modified to become the first fax machine, at first simply sent "long" and "short" lines, which a telegraph operator could interpret quickly. The process was a success and the electrochemical process it used was a major leap forward for future fax technology.

Bain later applied the chemical telegraph idea to sending images. To send rudimentary pictures, Bain made a copy of the picture in copper and then discarded everything except the actual lines of the picture he wanted to send.

His process next used a pair of pendulums, synchronized at a distance by an electromagnet. He fitted the pendulum with a contact beneath it and swung it over the copper picture. Each time the contact touched the copper image, it would send an electrical impulse racing over the wire to the identical synchronized pendulum swinging over some chemically treated paper. The chemical in the paper darkened when touched by the energized pendulum. Both the sending picture and the receiving paper moved beneath each pendulum by 1 millimeter following each pendulum swing, resulting in a "scan" of the original and a copy printed on the other end, which eventually resulted in the copper image from the sending pendulum being duplicated on the paper.

Bain used a solution of nitrate ammonia and purssiate of potash to treat the paper that received the picture. When touched by the electrical impulse, the solution decomposed leaving a bluish stain. This created the first fax pages.